Caspar David Friedrich and the Romantic Vision of Nature

Exploring the artist who shaped landscapes into realms of contemplation and reverence

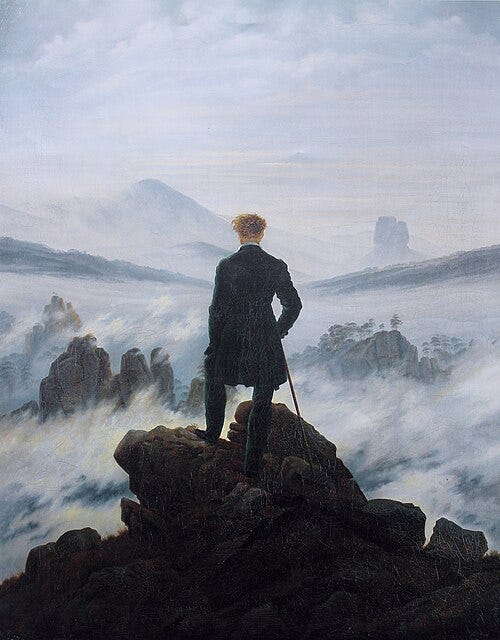

You stand at the edge of a rocky cliff. Below, clouds drift like waves over darkened hills. The wind is still. The horizon stretches endlessly, and the earth feels both immense and silent. Nothing moves but your thoughts. In that stillness, something awakens: a sense of being small before something immeasurably large. This quiet moment captures the essence of Caspar David Friedrich, a German painter who redefined how we experience nature through art.

Friedrich was born in 1774 in Greifswald, a town on the Baltic coast of what is now northeastern Germany. He studied at the Copenhagen Academy before settling in Dresden, where he spent most of his career. As one of the pioneers of the Romantic movement, Friedrich became known for his moody landscapes, often featuring distant figures, ruins, forests, and wide skies. Rather than focusing on historical or mythological subjects, he placed nature at the center of his work, using it to explore themes of solitude, memory, and the passage of time.

When the Landscape Speaks First

Before Friedrich, the landscapes in paintings were usually secondary. Artists used them as a backdrop for religious scenes, classical stories, or grand historical events. Friedrich changed that focus. In his works, the environment itself became the subject. Human figures appeared, but they were small, subdued and gave way to the landscapes before them.

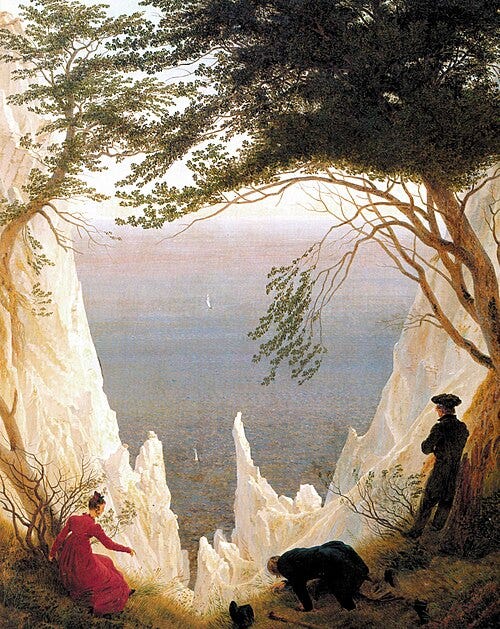

In Chalk Cliffs on Rügen (c. 1818–1819), three figures explore the edge of a cliff overlooking the Baltic Sea. Their postures suggest hesitation, but they are not the center of attention. Instead, strange, jagged cliffs and pale blue water dominate the canvas. As in much of Friedrich’s work, the emphasis shifts from what is happening to where it is happening, and how it makes us feel.

Finding the Sacred in the Natural World

Friedrich believed that nature was not just beautiful. It was sacred. He once wrote, "The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him." In his paintings, nature was felt both outside and inside of us. Forests, oceans, and skies became mirrors for the soul.

In Monk by the Sea (c. 1808–1810), a lone figure stands before a vast, empty ocean beneath an expansive sky. The landscape is stripped of detail and the space feels endless. Due to the contrast in scale, the monk seems almost to be swallowed by it. Yet he does not turn away. He remains still, facing the horizon. The painting does not tell a story in the usual sense. It presents a moment of quiet confrontation between the human presence and the infinite.

Ruins and Winter as Messengers of Time

Many of Friedrich’s paintings show ruins, tombs, or bare winter trees. These are not necessarily meant to feel hopeless. Instead, they ask us to reflect on time, memory, and the cycles of life. In Abbey in the Oakwood (c. 1809–1810), monks carry a coffin through snow toward the remains of a Gothic church. The trees are leafless, and the building is broken. Yet the composition is balanced and there is no sense of immediate threat.

Friedrich often used these settings to suggest that decay is not the end. The natural world continues. Light breaks through clouds. Snow melts. Even in death, there is dignity.

Turning Inward During a Time of Upheaval

Friedrich painted during a period of political and industrial upheaval. The Napoleonic Wars had swept across Europe. Cities were growing, machines were replacing hand labor, and traditional beliefs were being questioned. In this world of rapid change, Friedrich turned to nature and solitude.

His figures were not revolutionaries or heroes. They were monks, wanderers, and everyday people. They did not seek to control the landscape. They paused, observed and listened. Friedrich's art invites us to do the same.

In The Stages of Life (c. 1835), five figures stand on the shore beneath a vast sky, watching ships recede into the distance. Each person represents a different age, from childhood to old age. The ships mirror their life journeys, sailing outward toward the unknown. The painting does not dramatize change, but contemplates it. Like much of Friedrich’s work, it suggests that reflection, rather than reaction, allows us to meet time with dignity. In their stillness, his figures reflect a way of being present in the world that values attention over action and reverence over mastery.

Why His Quiet Vision Still Matters

Caspar David Friedrich gave landscape painting a new depth. His works are more than representations of trees or mountains. They are invitations to reflect, to wonder, and to feel; a quiet resistance to a world increasingly filled with noise and urgency. In his vision, stillness is not a luxury but a necessary refuge for the soul.