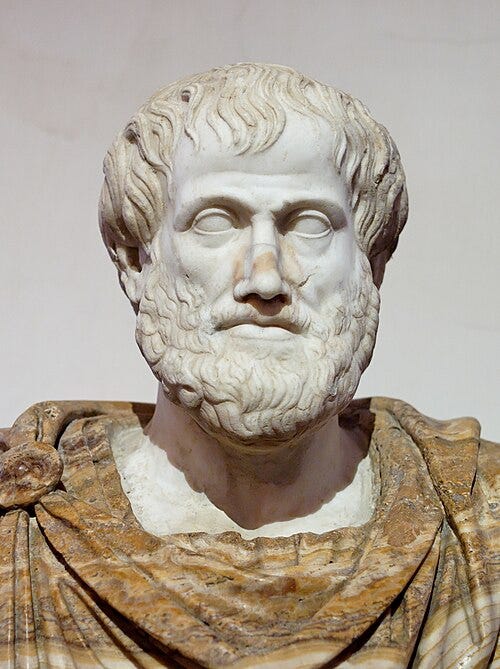

Great Thinkers Define Art: Aristotle

Exploring Aristotle’s view of art as both a reflection of life and a path to understanding ourselves

Aristotle was a student of Plato and tutor to Alexander the Great. He played a pivotal role in shaping the intellectual foundations of the Western world, with lasting contributions to logic, ethics, politics, biology, and aesthetics. Rather than looking beyond the world to ideal forms, like his teacher, Aristotle focused on the patterns of life itself. In all things, he searched for purpose, structure, and cause.

Aristotle understood art as a natural expression of the human mind. He placed it within the fabric of life itself, born from our deepest instincts: to imitate, to understand, and to find meaning in what we perceive. For him, art was a form of knowledge, parallel to philosophy, and grounded in the same fundamental drive to comprehend the world.

Imitation as insight

Aristotle’s most enduring ideas on art are found in the Poetics, a compact but influential treatise that focuses primarily on Greek Tragedy. In this work, he refines and deepens the ancient Greek concept of mimesis, or imitation. For Aristotle, imitation is not mechanical copying or deception. It is a natural part of the process towards proper understanding. Through imitation, the artist reveals not just what has happened, but what could happen, or what ought to happen, in light of human nature and inner necessity.

This marks a significant departure from Plato, who distrusted the arts for offering a mere shadow of reality. Aristotle, by contrast, affirmed their value. Humans, he observed, learn through imitation from an early age, and the arts elevate this instinct to produce profound insights.

Tragedy and catharsis

Of all the forms of art, Aristotle regarded tragedy with special reverence. He defined it as the imitation of a meaningful and complete sequence of events, serious in nature and carrying real consequences. When presented clearly from beginning to end, such stories evoke pity and fear, leading to a catharsis of those emotions. The term catharsis means a purification or release, and it points to art’s power to regulate emotional states and restore a sense of inner balance.

When the audience watches a noble figure brought down by error, weakness, or fate, they are not simply entertained. They are invited to reflect. Tragedy reveals the tensions at the heart of human life, such as how strength can fail and how even virtue may not guarantee a just outcome.

The tragic world is not reassuring. A single flaw, a misjudgment, or an unlucky turn can bring ruin to even the most admirable life. Tragedy does not offer comfort, but a recognition of life’s chaos. It asks us to confront the limits of control and, in doing so, deepens our understanding of what it means to be human.

Form, structure, and purpose

Aristotle believed that true beauty in art comes from structure and purpose. A great work is not a mess of feelings or action, but a unified whole. In the Poetics, Aristotle identified six essential elements that must be well-formed and well-ordered to create a powerful work of art:

Plot

The most important element. A well-structured sequence of events, complete and coherent, that unfolds through necessity or probability. Plot gives tragedy its soul.

Character

Secondary to plot, but essential. Characters reveal their nature through action, not mere description. Their flaws, choices, and missteps drive the story forward.

Thought

The ideas behind the action. Thought includes the moral, philosophical, or thematic content: what the play reveals about human nature, fate, or justice.

Diction

The expression of thought through language. Style, rhythm, and word choice elevate meaning and give the play its voice.

Melody

The musical quality of the performance, often carried by the chorus. Melody stirs emotion and deepens the atmosphere of the work.

Spectacle

The visual impact: costumes, staging, effects. While powerful, spectacle is the least essential. Without strong structure, it becomes empty display.

Art as a natural expression of the human spirit

Aristotle’s vision of art remains compelling because it affirms both reason and emotion. He did not elevate art above life, nor dismiss it as illusion. He placed it within the full range of human activity, as a way of knowing, a form of healing, and a mirror held up to human nature.

Art, for Aristotle, is an extension of what makes us human. It satisfies the same desire that leads us to seek knowledge and build communities. Whether through music, literature, or painting, we shape experience into form, and in doing so, we encounter our true selves.