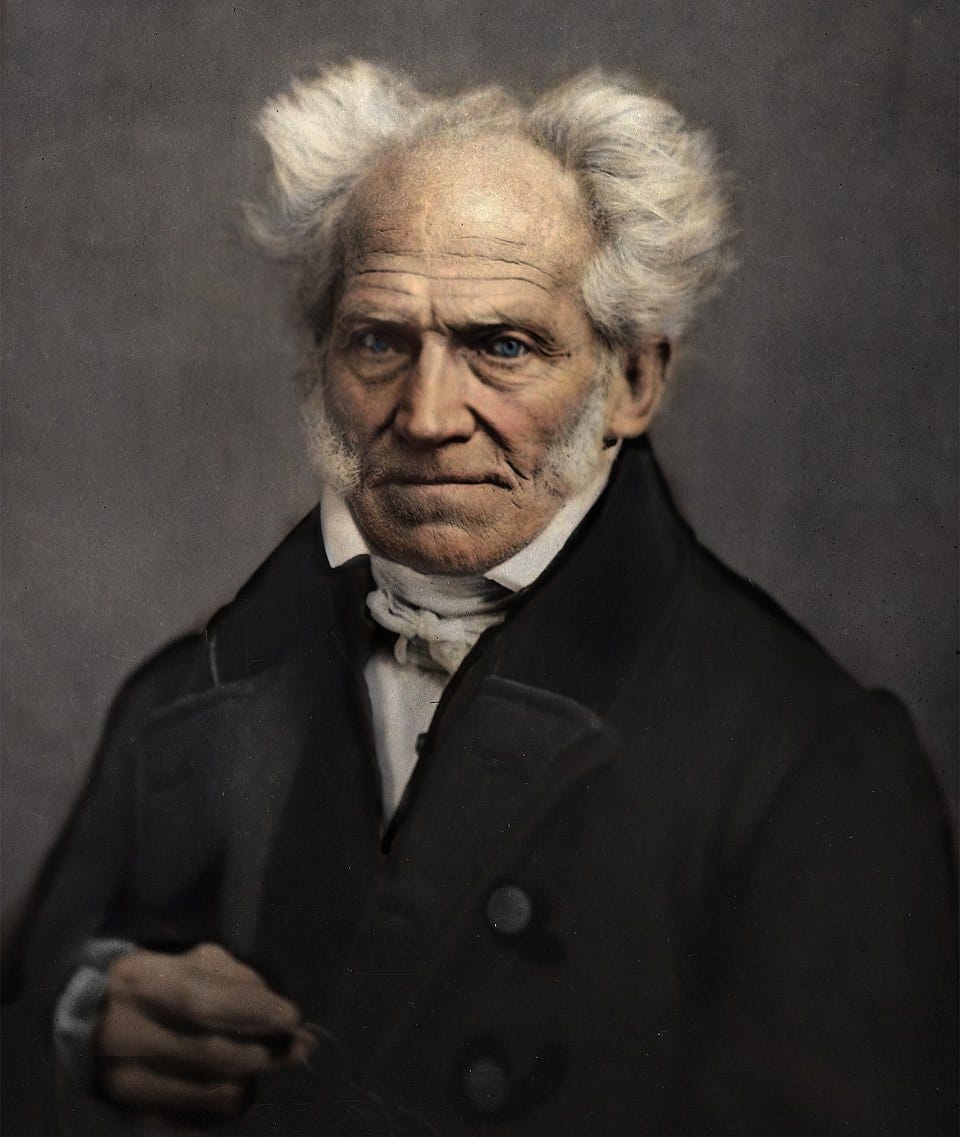

Great Thinkers Define Art: Arthur Schopenhauer

Learn how one of the most pessimistic philosophers ever saw the world and the role of art within it

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) stood as a shadow at the edge of Europe’s Enlightenment. While others celebrated reason, liberty, and progress, he saw something bleaker: a world governed by a blind, insatiable force he called the will. He offered no blueprint for utopia, no faith in political salvation or rational harmony. Instead, he became philosophy’s great pessimist, declaring that suffering was not a flaw in existence, but its essence.

Born in the wake of the French Revolution and shaped by the rigorous thought of Immanuel Kant, Schopenhauer came of age during an era of intellectual ferment. He fiercely opposed the optimistic idealism of contemporaries like G.W.F. Hegel, believing they obscured life’s harsher truths beneath abstract systems. Against this tide, he constructed a worldview both somber and sublime: a metaphysics of pain, and its antidote in aesthetics. This may all sound quite confusing, so let us examine Shopenhauer’’s philosophy more closely.

The World as Will and Representation

Drawing heavily from Kant, Schopenhauer accepted the idea that we do not experience reality as it is in itself, but only as it appears to us. He understood that everything we know is filtered through the limits of our senses, bound by the structures of space, time, and causality. Yet Schopenhauer went further. In his major work, The World as Will and Representation (1818), he argued that beneath this veil of appearances lies a deeper truth. Reality, he claimed, is not ultimately made of reason or matter, but of will—a blind, aimless force that drives all living things.

This will, he said, has no final purpose. It is simply the urge to go on, to push forward without end. In human beings, it shows itself as desire, hunger, ambition, and longing. And because it can never be fully satisfied, life becomes a cycle of frustration and fleeting relief. Pleasure quickly fades into pain, and when neither is present, boredom sets in. For Schopenhauer, this was the tragic rhythm at the heart of existence.

Yet he believed there were rare moments when a person could step outside this cycle, if only briefly. These were moments of aesthetic contemplation. He said that when absorbed in beauty we forget ourselves and the constant demands of the will.

Beauty Without Desire

Schopenhauer believed that art is powerful because it suspends the restless activity of the will. In everyday life, he explained, we see the world through the lens of utility. A tree becomes firewood, a face a potential partner, a mountain a source of raw materials. But in aesthetic experience, we observe without wanting. We contemplate without acting.

To explain this, Schopenhauer turned to Plato’s idea of ideal forms: that behind every material object lies a perfect, timeless essence, of which the visible world is only an imperfect copy. The artist, like the philosopher, catches glimpses of these forms and gives them shape. But while the philosopher uses reason, the artist works through intuition. The result is an image or sound that stills desire and invites quiet reflection. This mattered deeply to Schopenhauer, who believed that beauty arises when the viewer contemplates a Platonic Idea. For it is something universal and eternal, beyond the personal or practical.

Music as the Purest Art

Among all forms of art, music held the highest place in Schopenhauer’s thought. While painting and sculpture represent appearances, he believed that music alone expresses the will directly. It does not imitate the world. It gives voice to its inner structure.

A melody, for Schopenhauer, was not just a sequence of notes, but the audible form of emotion itself, be that grief, joy, longing, without need for words or images. Since music bypasses representation and speaks directly to the will, it moves us more deeply than any other art. It stirs the soul not through ideas, but through resonance.

This insight would later influence composers like Richard Wagner, who saw in Schopenhauer’s philosophy a justification for music as a kind of metaphysical truth. For them, music was not entertainment. It was revelation.

Beyond Art, Toward Compassion

For Schopenhauer, life was filled with futile striving and suffering, yet not entirely without dignity. He believed that through art, and through the ethical awakening that comes from understanding the suffering of others, we could quiet the will within ourselves. Compassion, born from the recognition that all beings are caught in the same striving, became his highest moral value.

Art, in this context, was not escape. It was resistance. A refusal to be consumed by appetite and illusion. In a world ruled by will, the artist becomes a kind of monk, seeking moments where striving ceases and something timeless and transcendent breaks through.

Schopenhauer’s vision is not a cheerful one, but it has a certain grace. He reminds us that even if we accept his world defined by suffering, there are peaceful moments. And those glimpses, however brief, are found in the contemplation of beauty.