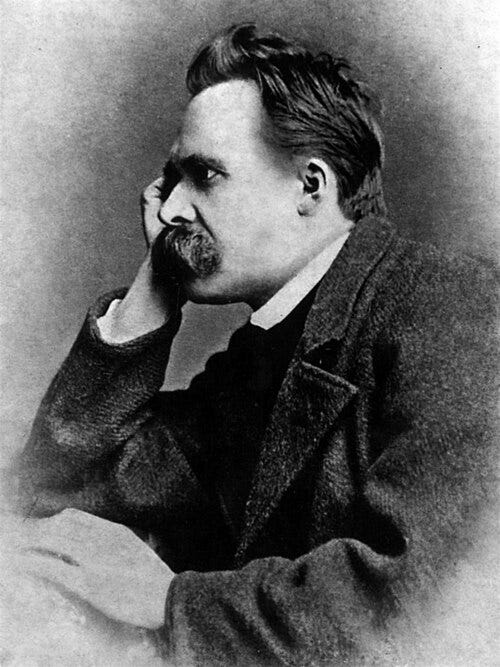

Great Thinkers Define Art: Friedrich Nietzsche

An exploration of aesthetic creation as a response to suffering, nihilism, and the collapse of metaphysical certainty

Friedrich Nietzsche believed that art was an essential part of human flourishing. In a world where belief in traditional religion was crumbling, he argued that art had to survive so that humanity could continue to endure harsh truths without collapsing into despair. For Nietzsche, aesthetic experience was the only force capable of making life meaningful in an age that had destroyed its own foundations for belief.

Born in 1844 in Prussia, Nietzsche lived through a time of enormous cultural change. Science and secularism were replacing theology and tradition. Confidence in absolute truth, divine morality, and metaphysical order was steadily weakening. What remained was a growing spiritual vacuum. In a section known as The Madman, Nietzsche has this character cry out: “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?” By this, Nietzsche did not mean that a deity had literally died, but that belief in the Christian God had lost its power to shape modern life. People continued to follow religious habits, but they no longer believed in the divinity behind them.

This loss, Nietzsche warned, would lead to nihilism, the belief that nothing matters and that all values are arbitrary. Religion had once explained suffering, rewarded obedience, and offered a clear moral direction. With that structure gone, who would guide the human soul? Nietzsche’s answer was radical. The artist would take up the role once held by the priest, to choose which values to esteem and foster them through culture.

Art as the new foundation of meaning

Nietzsche’s first major work, The Birth of Tragedy, explores how the ancient Greeks faced the chaos of existence. Greek tragedies, he argued, did not hide suffering, but embraced it openly. Through music, myth, and dramatic form, tragedy gave shape to pain and revealed the terrifying truths of life without retreating from them. According to Nietzsche, the Greeks were able to confront suffering artistically because of their excess vitality. They had the strength to face horror without needing to soften it. Their placement of every aspect of life into art was a form of vindication: “It is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.”

Though Nietzsche would later denounce his own book as “offensively Hegelian” for reducing art to a struggle between abstract opposites*, he initially saw two forces at the heart of art: the Apollonian, symbolizing clarity, form, and restraint, and the Dionysian, symbolizing chaos, ecstasy, and the breakdown of boundaries. These were necessarily in tension, with the Apollonian giving shape to the Dionysian depth and intensity. True art, he argued, arises when both are present, when form contains but does not suppress the wildness of life.

Among the arts, Nietzsche regarded music as the most immediate and potent expression of the Dionysian force. While painting and literature work closely with representation and description, music can evoke something more direct and participatory. It does not mirror the world but resonates with the underlying pulse of existence. For this reason, Nietzsche saw music not only as central to Greek tragedy but as the highest form of art. It does not filter experience through concepts. It speaks directly to the will, to the primal force that drives all becoming.

Schopenhauer, Wagner, and the rejection of escapism

Early in his career, Nietzsche was influenced by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, who believed that the world was driven by a blind, irrational will to survive. This basis developed into a pessimistic philosophy that posited the will as a force behind endless suffering. Schopenhauer thought art, especially music, could offer temporary relief by lifting us above this turmoil. For this reason, he became known as the musical philosopher.

Yet with time, Nietzsche became disenchanted with Schopenhauer, seeing his idea of escape as life-denying and premised on certain reductive, even erroneous propositions. He also distanced himself from the composer Richard Wagner, whose work he had once praised, for it was too closely tied to the philosophical and religious ideas Nietzsche aimed to overcome.

Eventually, Nietzsche made a full break away from transcendent values and metaphysics, calling instead for an affirmation of life grounded in human principles. He rooted this view in the concept of the will to power: the idea that living beings are driven not by mere survival, but by a deeper impulse to grow, to assert, and to overcome their own limitations. Grounding his vision in this natural drive, he declared: “What is good? All that heightens the feeling of power in man, the will to power, power itself.”

Art, he argued, should help us cultivate a healthy relationship with this force. It should not lead us to escape or renounce life, but to embrace its challenges and intensities. Nietzsche’s formula for his own happiness was simple but striking: “a yes, a no, a straight line. A goal.” The sickness of his age, he believed, stemmed from turning away from worldly power and projecting the will to power into another world.

The artist as the new craftsman of the soul

Nietzsche identified that throughout human civilisation the priest had been the figure responsible for shaping the soul, offering guidance, imposing rules, and interpreting suffering in light of divine justice. But at the heart of this process, he identified ressentiment: a deep, festering resentment toward strength, harbored by those who felt powerless. Through religion, the priest taught people to moralize their weakness, reshaping them to accept their lack of worldly power as virtue. Guilt and moral law redirected their instinct to punish away from their oppressors and inwards. This redirection of aggression became a kind of inverted power, with self-flagellation representing a moral triumph over instinct. Religion, in Nietzsche’s view, elevated humility, obedience, and self-denial, while condemning pride, strength, and joy.

Art, too, was once under the priest’s command. For centuries, the artist served religious ends, illustrating sacred stories and reinforcing theological order. The artist’s task was to make divine truth visible, but always under the authority of revelation. Yet as belief in God declined and the power of religious institutions eroded, the artist began to break free.

No longer an artisan bound to doctrine, the artist emerged as an independent creator, now capable of reordering values in accord with a more individualized vision. In this shift, Nietzsche saw more than aesthetic rebellion. He saw the possibility of overcoming the life-denial of two millennia. Where the priest once fashioned the soul through guilt and obedience, the artist could now reclaim that role through creation. By shaping experience into form and affirming life rather than denying it, the artist becomes the new craftsman of the soul.

A philosophy of transformation

Nietzsche feared that modernity would collapse into nihilism, producing the last man: someone who seeks only comfort and avoids all risk, challenge, and greatness. Yet he did not lament the death of God, as has become the popular view today. He saw it as an opportunity for transformation.

For Nietzsche, though art had been used to create an escape from life, it also offered the most profound way of engaging with it. He believed we must use it to confront suffering, affirm existence, and give shape to chaos. This is what makes art essential. It is not the decoration of a culture, but its foundation.

*Oversimplified, for brevity.