Great Thinkers Define Art: Leo Tolstoy

In an essay near the end of his career, Tolstoy reimagined art as a moral act, not a mere celebration of beauty

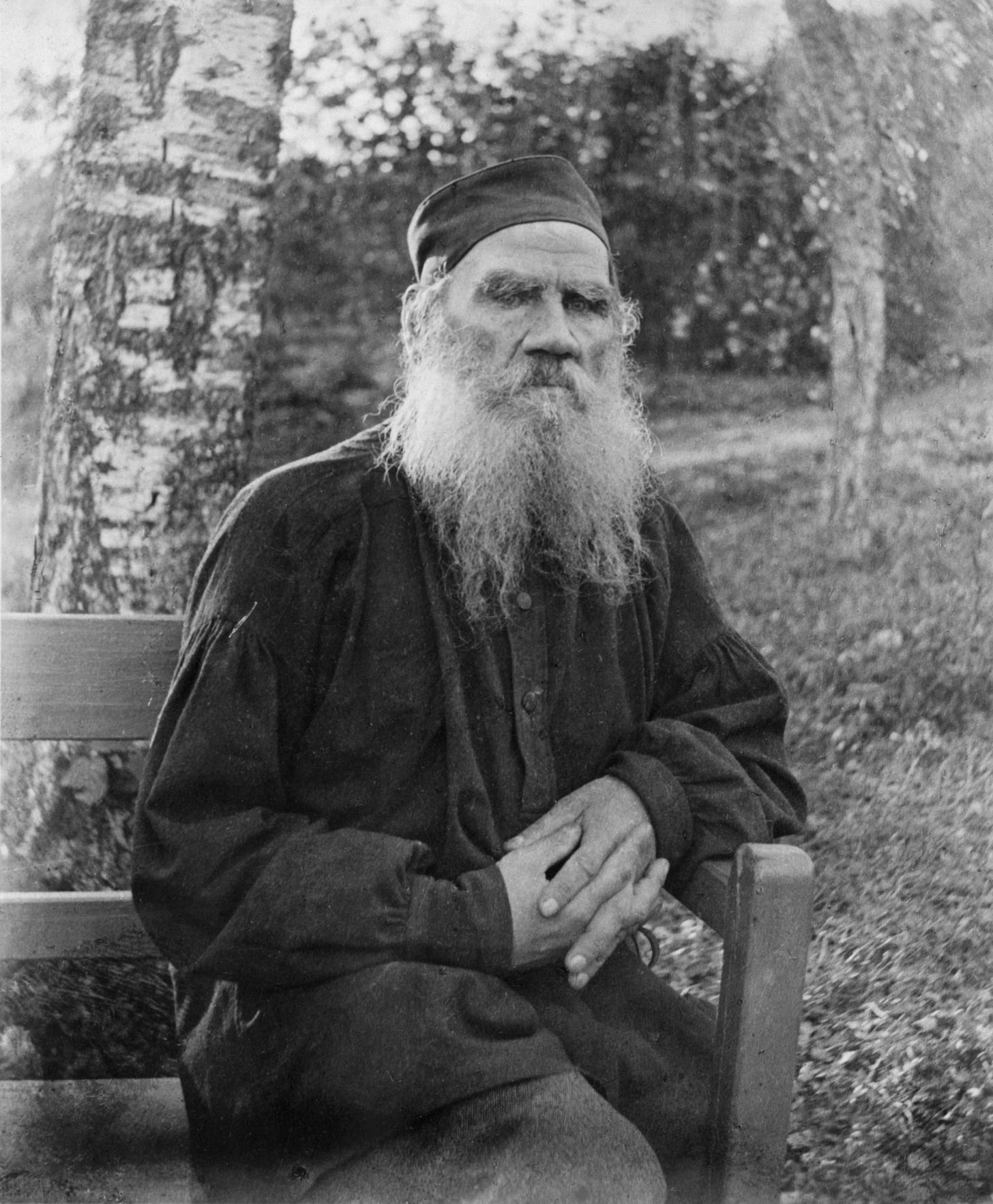

Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) was a Russian novelist, thinker, and moral philosopher. From the 1860s to the 1870s, Tolstoy secured his place among the literary giants, writing War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877). These were not only considered artistic triumphs but touchstones of Russian identity. Yet beneath his public acclaim, Tolstoy was growing increasingly troubled by the contradictions of his life. As a wealthy aristocrat and celebrated writer, he lived in comfort while many around him suffered in poverty.

This unease deepened into a full-blown spiritual crisis in the late 1870s, culminating in his confessional essay A Confession (written in 1879–1880). There, he described being tormented by the question of life’s meaning, and by the hypocrisy of a society that revered both wealth and religion while failing to uphold genuine moral values. Out of this turmoil, he embraced a radical form of Christian humanism that would shape all his later works.

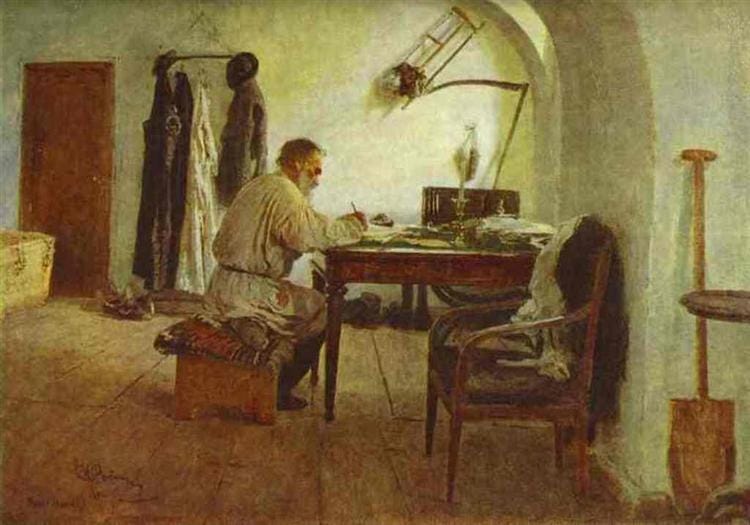

What Is Art? (1897), written two decades after his crisis, reflects this transformation. In it, Tolstoy rejected conventional standards of beauty, originality, and prestige, arguing instead that art should be judged by its ability to sincerely transmit feeling. He was particularly interested in feelings that fostered unity, compassion, and moral clarity.

Art as Transmission, Not Decoration

For Tolstoy, art was not solely about the creation of beautiful objects or impressive displays of talent. It was, at its core, a form of communication. True art occurred when one person experienced a deep emotion and succeeded in sharing that emotion with others. If the audience could feel what the artist felt and the emotion passed like an electric current between them, the work could be considered art.

Tolstoy firmly rejected the idea that beauty could be the true aim of art. He argued that beauty was not only subjective, but morally unreliable. The assertion that the aim of art is beauty is similar to saying the purpose of food is its pleasant taste. For him, to make beauty the standard was to elevate pleasure over truth, and superficiality over meaning.

This definition gave equal weight to a grand painting, a folk tale, or a lullaby. Technique was secondary to sincerity. Tolstoy believed that many revered artworks of his day, despite their technical brilliance, failed to communicate anything real or morally nourishing. Without emotional clarity, he argued, art became an ornament for the wealthy or a distraction for the bored.

The Waste and Immorality of Luxury Art

More than irrelevant, much of elite art struck Tolstoy as innately immoral. Lavish operas, ornate galleries, and state-sponsored performances consumed vast resources, including money, labor, and human attention. Meanwhile, the majority of people were left with no access to meaningful expression. In a world of poverty and suffering, such extravagance was not just a misjudgement of values, but a kind of theft.

Art, Tolstoy argued, had been hijacked by a leisure class. It no longer served the spiritual needs of the common person but instead became a mirror for vanity and cultural pride. Works that glorified war, romanticized despair, or indulged in luxury dulled the conscience and ignored the sacred purpose of art: to connect, to console, and to elevate.

Why Tolstoy Still Matters

Tolstoy’s views remain challenging, especially in our modern world which often prizes self-expression, innovation, and aesthetic freedom. His dismissal of figures like Shakespeare and Wagner may strike contemporary readers as severe, and his belief that art must serve clear moral ends can feel counterintuitive to those who see ambiguity, irony, or individualism as essential to creativity.

At a time when art is often shaped by profit, performance, and shock value, Tolstoy offers a radically different vision. For him, art does not exist in a vacuum. It is a moral act, a form of communion. His conception of good art is the art which transmits the simplest and most universally intelligible feelings. From this perspective, it is not a means of self-glorification, but a gift to others. Art’s purpose is not solely for the artist’s benefit, but to bind people together through shared feeling and moral clarity.