How Cubism Shattered Reality and Rearranged the World

A look at how Cubism broke with tradition and reimagined what art could show and express

In the early 20th century, the world was entering a new age. Cities lit up with electricity, machines transformed labor, and photography began to reshape how people saw the world. At the same time, scientific discoveries were challenging traditional understandings of time, space, and matter. In this environment of upheaval, a new form of art emerged that broke from centuries of tradition. Cubism, led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, did not aim to reflect the world as it appeared to the eye. Instead, it reassembled reality from multiple angles at once, creating a fractured but thoughtful new way of representing the world.

The Birth of the Movement

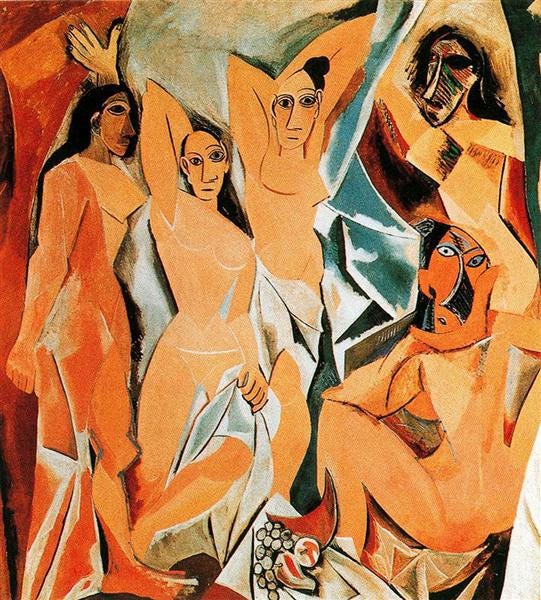

Cubism began around 1907 in Paris with Picasso’s groundbreaking painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Influenced by African sculpture and the late work of Paul Cézanne, Picasso moved away from naturalistic form. His figures became angular and flattened, with faces resembling masks rather than realistic portraits.

Soon after, Georges Braque joined Picasso in exploring this new approach. Together, they developed what became known as Analytical Cubism. In works like Violin and Palette by Braque (1909) and Girl with a Mandolin by Picasso (1910), objects were broken into overlapping planes in muted tones, their forms shattered and reassembled to reveal multiple angles at once.

Rather than offering a single viewpoint, these early Cubist works presented multiple perspectives in one image. Shapes overlapped and interlocked, with earthy colors and dense compositions that focused heavily on structure. This was not art solely for decoration, but a visual investigation into how we perceive the world.

A New Visual Language

Cubism introduced a new approach to visual thinking. Instead of mimicking reality through depth and shadow, artists flattened space, treating the canvas as a surface for conceptual exploration. Viewers were encouraged to piece images together mentally, engaging with their layered forms.

This shift can be seen in Picasso’s The Accordionist (1911), a dense composition of angular shapes and layered planes. The image offers no clear subject, only a network of forms that hint at an underlying structure.

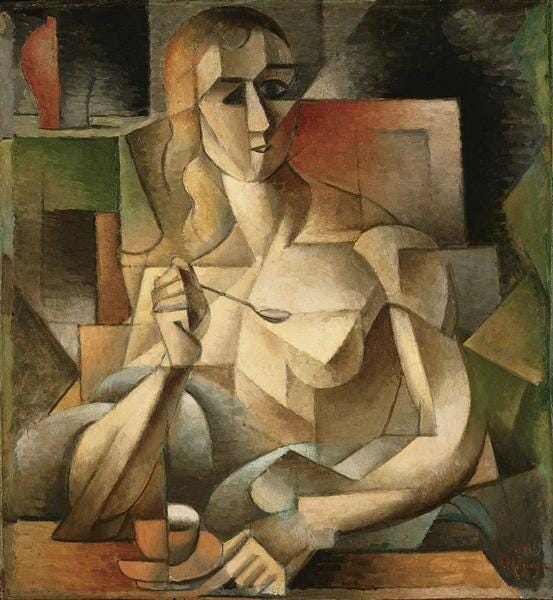

Artists across Europe soon adapted Cubist techniques. Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger helped promote the movement through both painting and theory. In Tea Time by Metzinger (1911), the viewer encounters a quiet domestic scene restructured into a network of flat planes and intersecting forms.

Color Collage and the Rise of Synthetic Cubism

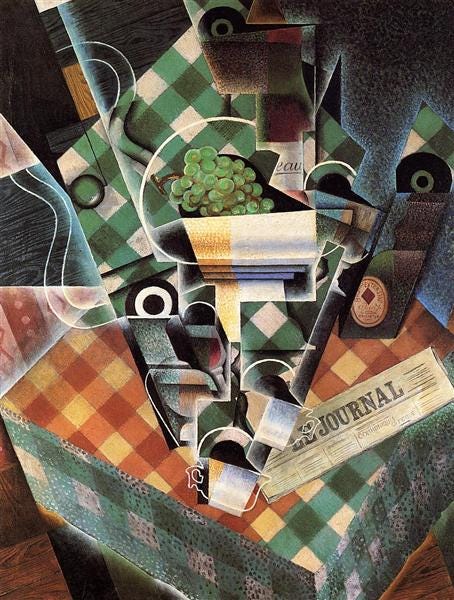

Around 1912, Cubism entered a new phase. Known as Synthetic Cubism, this style introduced bolder colors, simpler shapes, and the use of real-world materials. Collage became a key technique, blending paint with paper, newspaper, and printed textures.

Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1912) was one of the first artworks to incorporate collage. It includes an oilcloth printed with a cane pattern, surrounded by rope and painted forms. This merging of illusion and object challenged what a painting could be, and brought everyday materials into the realm of high art.

Juan Gris also embraced this evolution. In works like Still Life with Checked Tablecloth (1915), he combined vivid color, legible objects, and carefully structured design. Bottles, fruit, and folded newspapers are stylized but still recognizable, arranged with a sense of harmony that contrasts with the dense fragmentation of earlier Cubism. While Picasso and Braque often leaned into ambiguity, Gris emphasized clarity and visual rhythm, showing that Synthetic Cubism could be both complex and composed.

The Lasting Impact and Legacy of Cubism

Cubism changed the direction of modern art. It challenged the idea that art should imitate nature and introduced a way of thinking that emphasized construction, perception, and abstraction. The movement influenced sculpture, design, film, and literature. It encouraged reality to be questioned, reshaped, and reimagined.

Far more than a passing trend, Cubism marked a permanent shift in visual culture. It offered a new understanding of the world: one that embraced complexity, movement, and uncertainty. At a time when society itself was being reshaped, Cubism helped art keep pace with the future.