How Impressionism Broke Away From Tradition

The artistic movement that brought us out of studios and academic tradition and into the world of nature

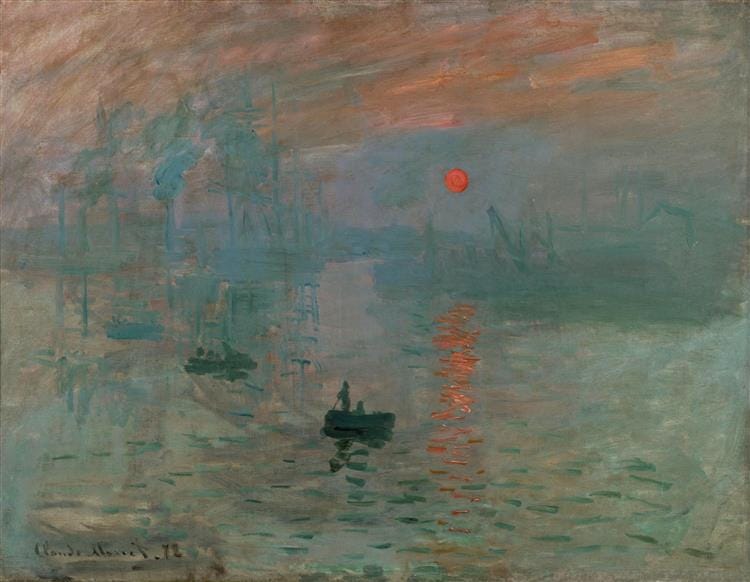

On an early morning in 1872, the sun rose over Le Havre’s harbor, bathing the sky in molten orange and deep blue. The artist Claude Monet stood beside the water, aiming to capture the morning haze with loose, vibrant strokes that prioritized atmosphere over structure. He worked quickly, chasing the shimmer on the water before it changed. Monet called the piece ‘Impression, Sunrise.’ When the work was eventually shown at an independent art exhibition in 1874, a critic seized on its title and applied it mockingly to the entire group, calling them "Impressionists." Subsequently, the painting became recognised as the first example of impressionism.

Though this approach to painting scenes is now relatively common, it was a dramatic departure from the conventions of the time. Impressionism arrived not as quiet evolution, but as a rupture. It broke the rules, rejected tradition, and turned away from the ideal toward the fleeting. In doing so, it redefined the artist’s role, the nature of beauty, and the purpose of art itself. This was not about mastering the past, but rendering the present: chaotic, moving, alive. The Impressionists asked what it meant to truly witness a moment.

The Values Enforced by the Artistic Establishment

For centuries, the Académie des Beaux-Arts had defined good taste. Its doctrine elevated paintings of history and myth to the highest rank, followed by portraiture, genre scenes, landscapes, and still life, a rigid hierarchy of prestige. The Salon dictated success or obscurity, and rejection would be disastrous to one’s career.

Under this paradigm, art was required to adhere to noble, instructive, and refined standards. Painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau rendered mythological scenes in porcelain tones, their women idealized in timeless scenes. Perfection and moral clarity were the goals.

To achieve this polished ideal, artists worked in studios under carefully controlled lighting. Figures were posed with precision, compositions sketched and resketched, and brushwork smoothed to near invisibility. Natural light was considered too unpredictable, so painting outdoors was virtually unheard of. The studio was a sanctuary of order, where every element served the pursuit of harmony, ideal beauty, and narrative clarity.

A Rebellion Against the Status Quo

In 1866, Monet presented Women in the Garden. He had labored to capture the sunlight filtering through foliage as it touched the folds of white dresses, but the critics were not impressed. They scoffed at the loose brushwork, the lack of a clear narrative, and the absence of moral clarity. To them, it looked unfinished and even careless, a rejection of academic ideals. These criticisms foreshadowed the movement which would soon arrive in full force.

A growing circle of painters, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot shared Monet’s desire to escape the rigid rules of the Salon and pursue a more liberated form of expression. Throughout the late 1860s and early 1870s, they painted outdoors, using quick strokes to capture light, movement, and scenes from modern life. This allowed them to capture the shifting moods of nature with immediacy and vibrancy. The resulting paintings felt alive, infused with the atmosphere of the moment they portrayed.

The Artists Who Created the Movement

Although Monet remains the most widely known, Impressionism was never the work of a single painter. It was a movement shaped by many voices.

Edgar Degas, a master of capturing movement and modern life, painted ballerinas mid-practice and behind the scenes of the stage. Camille Pissarro and Pierre-Auguste Renoir explored the changing light of gardens, boulevards, and rivers, each with a distinct sense of atmosphere and rhythm. Berthe Morisot focused on women and children, using rapid brushwork and bold composition to bring quiet domestic moments to life.

Mary Cassatt, an American artist working in Paris, brought new depth to the movement through her depictions of motherhood and interior life. Her work added contrast to the more public subjects favored by her peers. She collaborated closely with Degas and played a key role in introducing Impressionism to American collectors, helping the movement gain international influence.

What We Can Learn From Impressionism

Impressionism reminds us that the world is always in motion and that beauty often lives in the fleeting moments. To paint an impression is to follow intuition and immediate perception, allowing the artist to let go of perfection. Through looser brushstrokes and fewer rules, Impressionism offered a new kind of artistic freedom and creativity.