How Realism Gave a Voice to the People

The era when painters abandoned idealism, defied authority, and found beauty in ordinary lives

In the mid-nineteenth century, the art world underwent a quiet revolution. For centuries, painting had served the lofty purposes of Church and Empire. Artists were expected to glorify gods, saints, kings, or mythic heroes. But in the wake of political upheaval and industrial change, a new vision began to emerge. It was grounded, confrontational, and profoundly human. Realism, as it came to be called, turned its gaze away from the heavens and towards the world as it was.

At its heart, the movement was political. Realist painters did not seek to flatter the elite, but expose the realities of their time: often ugly, often unjust. Through this process, they bestowed dignity on those who had long remained unseen.

Painting the People

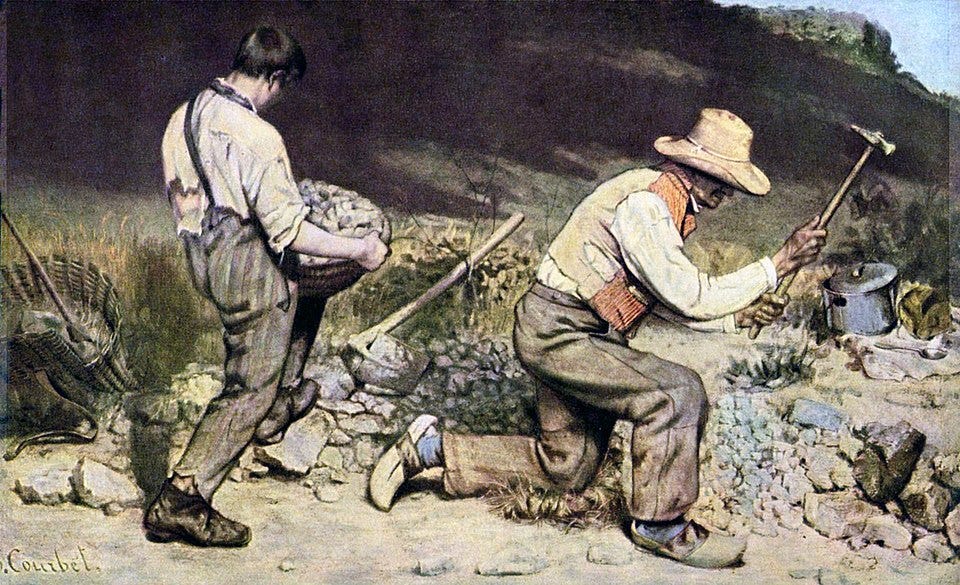

One of the clearest voices in this movement was Gustave Courbet. His painting The Stone Breakers caused a stir due to its subject matter. It showed two workers, one young and one old, crushing stones along a rural road. There were no symbols of virtue, no dramatic poses or romantic lighting. Just worn clothes, muted colors, and the weight of physical toil. In this image, Courbet made a radical claim: that the lives of common people were worthy of art.

Courbet’s work rejected the idea that beauty must be found in an ideal. He suggested that beauty could be found in an honest rendering of a moment, no matter how ordinary or harsh. This vision struck at the heart of an art world still dominated by aristocratic tastes. It also aligned with rising democratic movements across Europe, especially after the revolutions of 1848 where citizens demanded greater rights, freedoms, and representation.

A Rural Resistance

Jean-François Millet took a similar approach. His painting The Gleaners depicts three peasant women collecting leftover grain after a harvest. The task is unglamorous, yet necessary. In the distance, a loaded cart rolls away under the watch of landowners and hired men. The contrast is stark. The women work for scraps while the harvest is claimed by others. This tone is deepened by the muddy, realistic colors.

Millet offered the respect and dignity of paying witness. Born into a farming family, he painted rural life with the familiarity of someone who had lived it.

The Weight of Labor

Léon Augustin Lhermitte observed rural life with an unwavering focus on realism. His scenes are spare and grounded, depicting everyday people whose labor shapes their bodies and defines their days.

In Apple Market, Landerneau, Brittany, Lhermitte depicts a dynamic moment of village life, with a small crowd, strewn apples and conversation. Stone buildings with slate rooftops enclose the scene, not decorative, but practical. The casual poses create a sense of close-knit community.

Lhermitte gives the scene space to breathe, without editorializing or adding drama. He simply shows people immersed in daily life. In this way, Lhermitte honors Realist art’s promise to give worthy form to lives often overlooked.

Realism as Defiance

Realism also challenged the institutions that decided what art should be. The Salon, controlled by the French Academy, favored smooth brushwork, noble subjects, and idealized forms. In contrast, Honoré Daumier focused on the everyday world, depicted with rough textures and sketched elements. His drawings and lithographs showed how ordinary people lived.

The Third-Class Carriage, shows a crowded railway car, dimly lit. A mother cradles her child, a tired woman sits beside her, and an elderly man leans forward in thought. Their clothes are plain, their faces marked by fatigue. There is no drama, no theatrical lighting. Just stillness, weight, and the shared experience of ordinary people moving through a rapidly changing society.

Daumier’s strength was his ability to observe without exaggeration. Through simple gestures and careful composition, he made visible the lives that official, curated art ignored.

The Legacy of Seeing Clearly

Though Realism eventually gave way to other movements such as Impressionism, Symbolism, and Modernism, its impact endured. It opened the door for artists to speak directly to their time. In doing so, it democratized art and elevated honesty above romanticization. It affirmed that labor mattered just as much as leisure, and that the faces of people working fields and factories were no less worthy of remembrance than those in palace halls.