How Renaissance Art Redefined Power and Politics

Exploring the ways that collaboration between artists and patrons shaped the politics and ideals of the Renaissance period

You are Michelangelo. In the courtyard of Florence’s cathedral workshop, you stand before a rough block of marble that has been left untouched for years. Other sculptors have already dismissed it, finding too many imperfections and deeming it too unwieldy for a monument, but you see the potential. With chisel in hand and a vision, you carve David. Not a saint, nor a king, but a young man prepared to face Goliath. His proportions and gesture convey the strength and vitality attainable by humanity.

In Renaissance Italy, art was not only about beauty. It was a way to communicate power and influence the public imagination. City-states like Florence, Venice, and Rome became stages where politics played out through paintings and sculptures. Rulers and patrons commissioned art to bolster their image and maintain control. Artists drew from classical ideals and a human-centred philosophy to achieve this. Their creations weren’t always just about flattery. Often, they invited questions and conversation.

Join us on a journey through the Renaissance and its radical new idea: that authority could be grounded in the dignity of man, not solely the commands of heaven.

The Rebirth of Classical Ideals

In the medieval world, political authority was grounded in divine hierarchy. Kings ruled by the grace of God, and the Church stood as the supreme guardian of truth and order. Human life was understood primarily through the lens of sin and salvation, with obedience to divine law as the measure of virtue. The Renaissance marked a significant shift, rooted in the philosophy of past ages. In forgotten manuscripts by Cicero, Plato, and other classical thinkers, scholars encountered a vision of humanity rooted in reason, dignity, and moral agency. From this revival emerged humanism. This movement did not discard religion, but it placed human potential at the center of intellectual and cultural life.

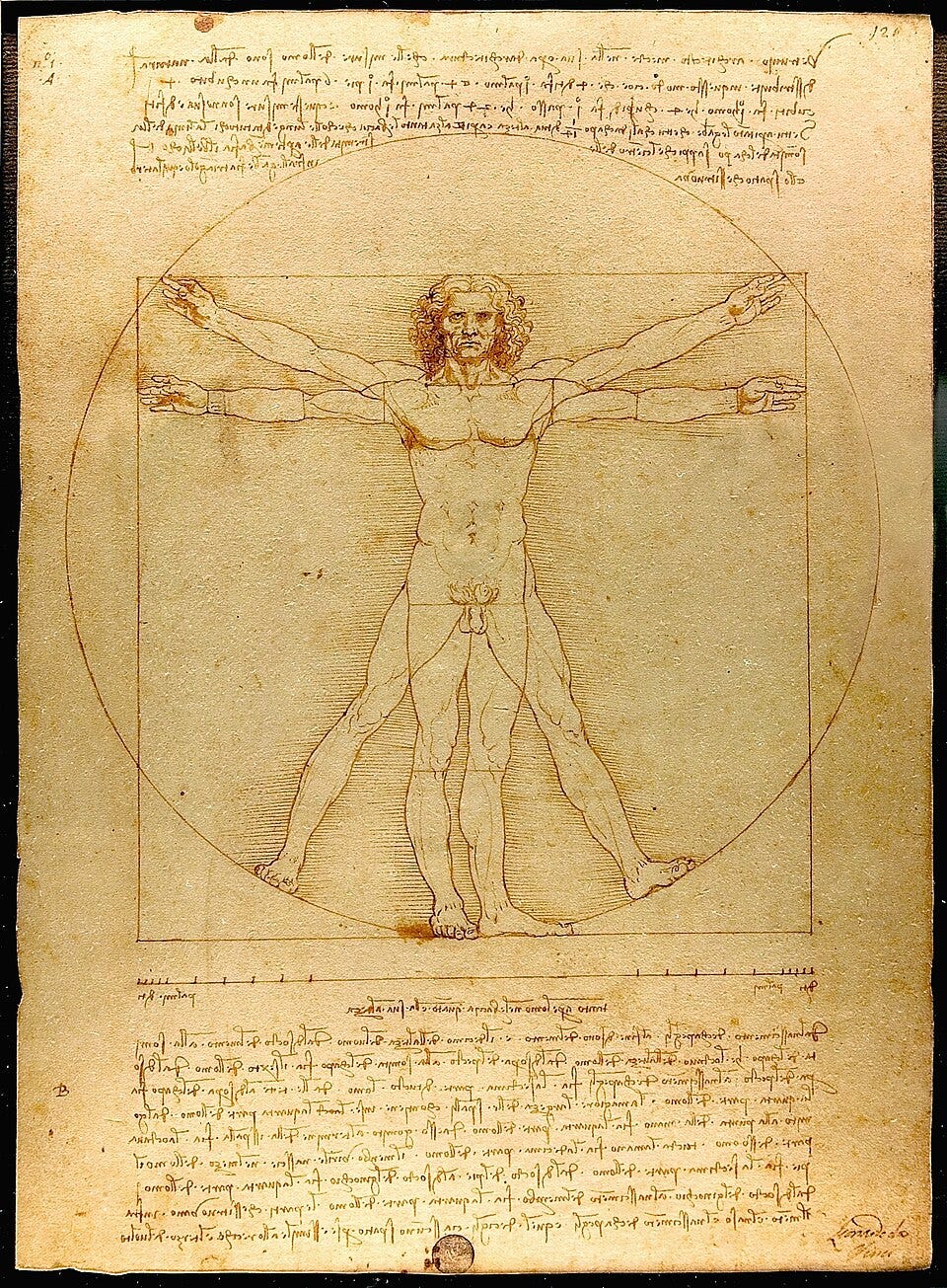

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man embodied the ideals of the time: a well-proportioned human figure aligned with geometric principles, suggesting a profound harmony between man and the cosmos.

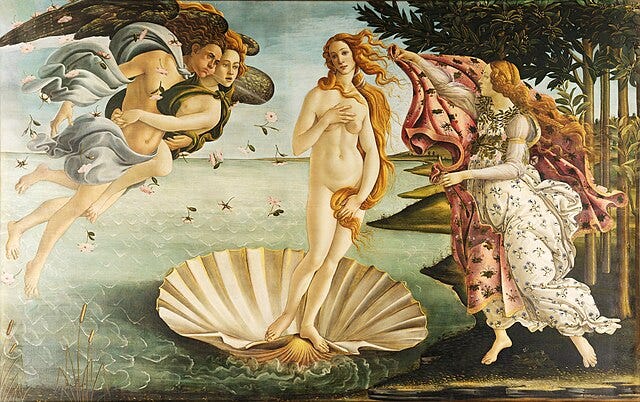

Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus reimagined divine beauty through the lens of classical mythology, placing grace and proportion at the heart of spiritual symbolism.

Raphael, in his fresco The School of Athens, depicted the ancient philosophers beneath an idealised architectural space, drawing a connection between the heights of intellect and order.

The Politics Behind the Movement

Behind nearly every great work of the Renaissance stood a ruler, a banker, or a pope, who used art to shape how they were seen and remembered. Patronage was not simply an act of charity; it was a strategic act, creating an image of authority for the patron.

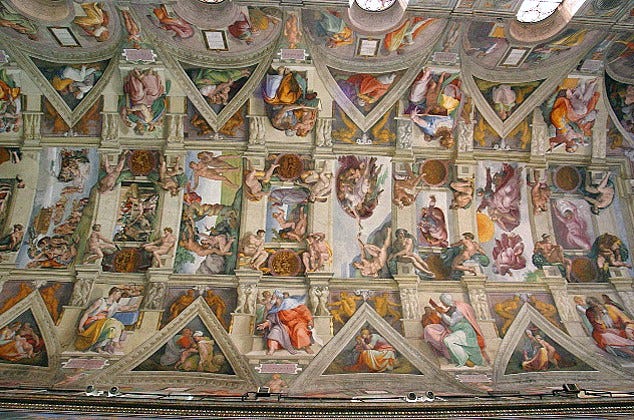

In Florence, the Medici family mastered this craft. Despite not being royalty, they used commissions to build a legacy of wisdom and cultural authority. The artist, Sandro Botticelli painted their likeness into sacred scenes. Meanwhile in Rome, Pope Julius II employed artists like Raphael and Michelangelo to remake the Vatican into a theatre of divine rule. Ceilings, walls, and corridors became visual sermons, affirming his power in the language of beauty.

The Artist as a Political Actor

During the Renaissance, artists stepped out of the shadows of anonymity. No longer seen as only craftsmen, they became public figures and intellectuals. Their work extended beyond technical skill to shape reputations, advance ideas, and influence the political and philosophical life of their time.

Leonardo da Vinci served dukes, kings, and noble patrons across Italy and France, not only as a painter, but as a military engineer, architect, and advisor. His notebooks are filled with studies of anatomy, mechanics, flight, and illusion, with drawings ranging from weapons of war to stage designs. In his lifetime, he moved between courts with the status of a diplomat, admired for the breadth of his knowledge as much as for his artistic genius. His career embodied the Renaissance ideal: a life in which art, science, and intellect could be woven into one pursuit.

Power Redefined and Reimagined

In the hands of Renaissance artists, rulers were cast as heroes and values of justice, wisdom and courage were elevated. What once belonged exclusively to the divine now appeared in the confident gaze of David, in the measured symmetry of the Vitruvian Man, and in the grandeur of painted chapels. Many of these works still influence how we picture strength and virtue today.

Renaissance art embodies a shift in the very idea of power: from something inherited by divine right to something crafted through intellect, imagination, and form. What endures is not only incredible art, but an inspiring vision of human potential.