Painting Dreams and Subconscious Desires Through Surrealism

Exploring the Art Movement That Turned Dreams, Symbols, and the Subconscious into Visual Language

In the aftermath of World War I, a deep cultural wound was opened across Europe. Artists and writers, disillusioned by reason and devastated by violence, sought new ways to explore the human experience. Out of this unrest emerged Surrealism, an artistic and literary movement that rejected logic and embraced the illogical, the dreamlike, and the irrational.

Founded in Paris in the 1920s, Surrealism was not just an aesthetic but a philosophy. It was a revolt against the constraints of reason and a dive into the unexplored depths of the subconscious mind. Inspired by Sigmund Freud’s theories of dreams and the unconscious, surrealist artists set out to depict inner realities that were more vivid and strange than anything in the waking world.

Origins in Dada, Freud and the Unconscious

Surrealism developed from Dadaism, a radical anti-art movement that arose during World War I. While Dada attacked traditional art through chaos and absurdity, Surrealism aimed to construct a new kind of truth. The movement was formally launched in 1924 when poet André Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto. He called for “pure psychic automatism,” meaning the free expression of thought unfiltered by logic or morality.

Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theories gave Surrealists a framework for exploring dreams, repressed desires, and childhood memories. They believed rational thought limited creativity, and that deeper insight could be found through the irrational workings of the mind. The result was a body of work that felt more like a set of visions than traditional compositions, often manipulating ordinary objects in strange and mind boggling ways.

Artists Who Shaped the Movement

No name is more closely associated with Surrealism than Salvador Dalí, whose melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory (1931) became a symbol of distorted time and psychological tension. Dalí’s painting style gave his dreamlike imagery a strange credibility, making the irrational appear tangible. While his theatrical persona often overshadowed his work, his renderings of the subconscious with vivid clarity helped define the visual language of Surrealism.

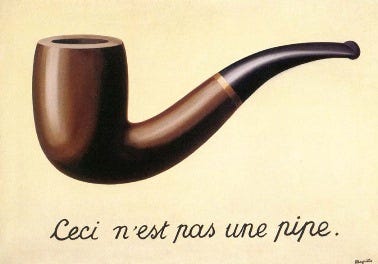

René Magritte took a different approach, using simple images to question how we see and understand the world. In The Treachery of Images (1929), he painted a pipe with the caption “This is not a pipe.” The point is simple, so simple that it is often taken for granted. what we see is just a picture, not the real thing. Magritte’s work reminds us that words and images are not reality, even if we treat them that way.

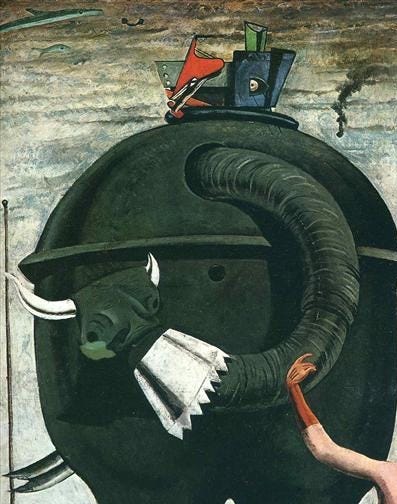

Other significant artists include Max Ernst, who used techniques like collage and frottage to create eerie hybrid forms, and Yves Tanguy, whose barren dreamscapes feature strange, organic shapes that defy identification. Each of these artists sought to expand the boundaries of what art could express.

Techniques and Themes of the Surrealists

Surrealist artists developed creative methods to bypass the conscious mind. Techniques like automatic drawing, where the hand moved without rational control, and the collaborative game “exquisite corpse” were designed to unlock spontaneous expression. André Masson used automatism to produce swirling, instinctive images like Battle of Fishes (1926). Similarly, Roberto Matta visualized shifting dream-architectures, as seen in Invasion of the Night (1941).

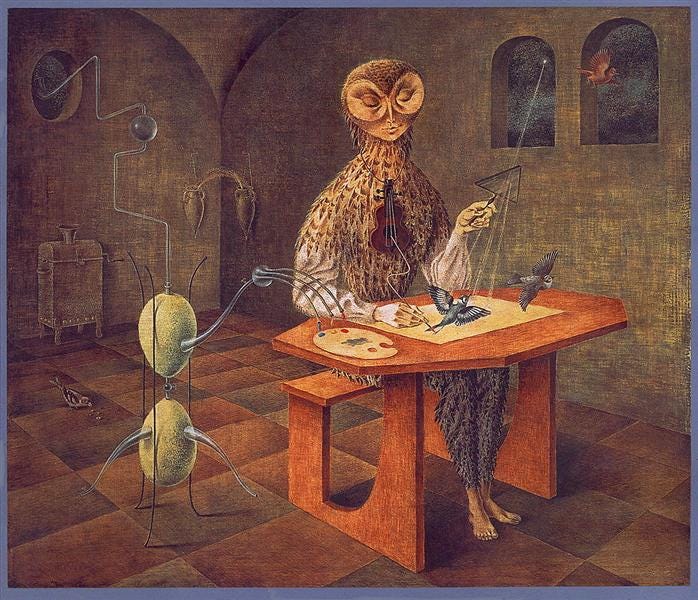

Common themes in Surrealism include dreams, metamorphosis, decay, and the absurd. Familiar elements often appear in eerie or contradictory settings. In The Pomps of the Subsoil (1947), Leonora Carrington depicts spectral beings gathered in a strange ritual, blending myth, nature, and inner symbolism. Remedios Varo, another key figure, created intricate, mystical environments where women appear as scientists, magicians, or alchemists. Her painting Creation of the Birds (1957) shows a cloaked figure painting birds that come alive, blurring the line between creation and transformation.

These works rarely follow clear narratives. They aim to provoke emotion, suggestion, or unease, rather than offer answers. For the Surrealists, art was not about mirroring the external world but exposing hidden psychological realities. Their goal was to merge opposites, conscious and unconscious, reason and fantasy, to produce a more fluid communication of ideas.

The Enduring Influence of Surrealism

Although the movement lost momentum after World War II, Surrealism left a lasting legacy. It helped redefine the purpose of art, encouraging future artists to explore psychological inner states. Movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art absorbed its experimental spirit. Surrealism also influenced cinema, literature, and even advertising with its vivid, dreamlike logic.

Surrealism was more than a visual experiment. It challenged conventional ways of seeing and asked viewers to look beyond appearances, to confront what often remains hidden: desire, fear, memory, contradiction. The movement did not offer answers but instead presented open-ended images that disrupt expectations and prompt reflection.

From melting clocks to impossible architecture, Surrealism reminds us that the mind is not a perfect mirror of the world, but may be a window into something more profound.