The Dramatisation of Greek Myths in the Hellenistic Period

Exploring How Hellenistic Sculptures Imbued the Divine Figures of Myth With Depth and Humanity

Following Alexander the Great’s conquests, the Greek world was broken apart, expanded, and reshaped into something new: cosmopolitan and deeply human. During this turbulent dawn of the Hellenistic period (c. 323 to 31 BCE), Greek myths, once symbols of divine harmony and heroic perfection, began to feel more immediate and alive. Sculpture had embodied serene, stable ideals in the Classical era. The Hellenistic period, in contrast, emphasized expression and theatricality.

From Marble to Mirror

Classical sculpture celebrated the balanced, unyielding beauty of Apollo and Athena through harmonious proportions, poised stillness, and idealized form. The Hellenistic age introduced a new aesthetic, where harmony gave way to drama, dynamism, and psychological depth. Figures bled, struggled, aged, and cried.

This emotional realism mirrored a broader shift in the Greek psyche. No longer united by a single city state or ideal, people of the Hellenistic world lived in sprawling kingdoms, under foreign rule, surrounded by unfamiliar cultures. In this world, myth became more personal and moved away from centralised ideals.

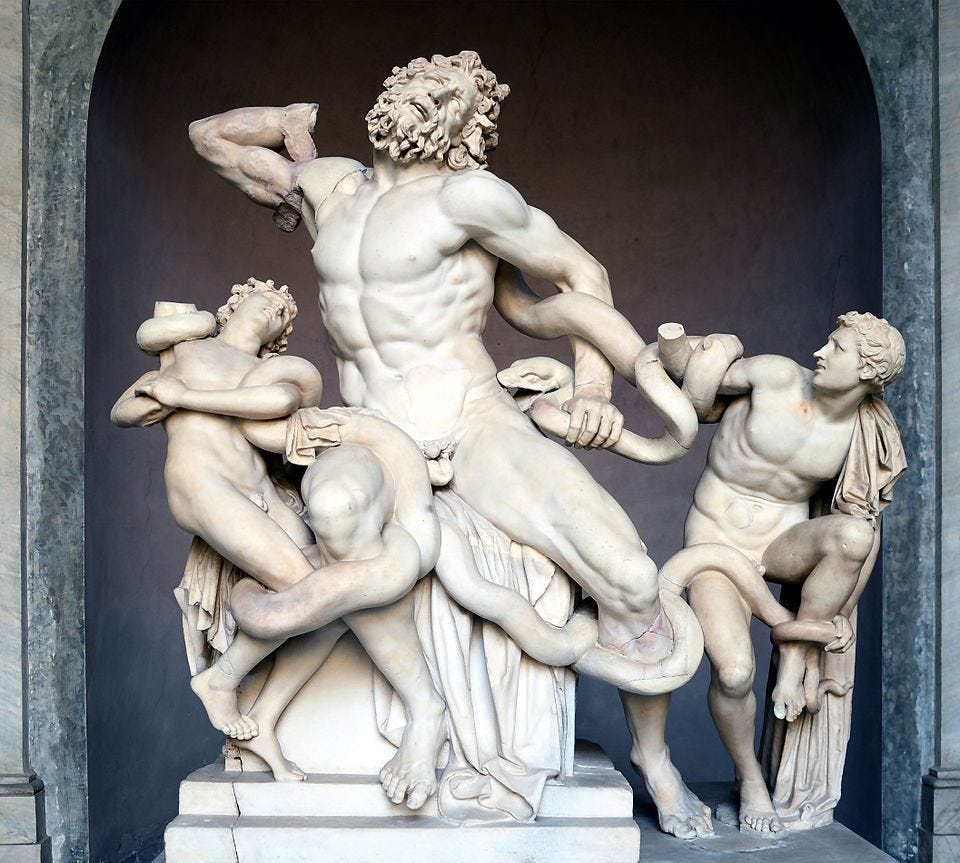

According to myth, Laocoön was a Trojan priest who warned his fellow citizens not to bring the Greek wooden horse into the city of Troy. “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts,” he cautioned. The warning defied the will of the gods, since they favoured the Greeks and wanted the plan to proceed. As punishment, two giant sea serpents rose from the depths and strangled him and his sons. In the sculpture Laocoön and His Sons, this moment is captured with striking intensity: muscles tense, serpents wrapped tightly around limbs, a father fighting to protect his children as they struggle beside him. It is not a scene of harmony, but of desperation and pain, frozen in marble. The gods do not offer salvation. They deliver judgment.

The Humanization of Myth

The Hellenistic artist turned myth inside out. No longer was Heracles the invincible strongman. He could now be shown weary, drunk, or dying. Pathos, meaning the artistic expression of deep emotion, became the new divine language. Even Ariadne, once the clever helper of Theseus, is shown asleep and abandoned, in a position betraying vulnerability.

Though not a figure from mythology, the sculpture Dying Gaul depicts a wounded Celtic warrior, collapsed on the ground, his head bowed and body bleeding. Fallen, yet dignified, he occupies a place in sculpture once reserved for gods and heroes.

In these works, myth was not escape. It was a reflection of a world where certainty had been lost and gods seemed closer to mortals than ever before.

Myth and Politics Collide

The Hellenistic use of myth was not only emotional. It was political. Rulers across Egypt, Asia Minor, and Greece invoked myth to legitimize power and elevate their rule. The Great Altar of Pergamon, built in the 2nd century BCE by the Attalid dynasty, served as a prime example. Its Gigantomachy frieze (a decorated section that ran along the base of the altar, depicted the epic battle between the Olympian gods and the Giants. This was more than religious homage. It was imperial spectacle. Athena battled with explosive force, her drapery flaring like a war banner, casting the gods as agents of order and the giants as symbols of chaos. The imagery served as a clear metaphor for the enemies of the Pergamene state.

This was statecraft in sculpture. By aligning themselves with divine victors, Hellenistic kings claimed divine right and moral superiority. Stories that had once been told through painted pottery were now displayed on a grand scale, carved into massive stone altars and temple walls for all to see.

Sculpture as Storytelling

Hellenistic sculpture appears like a frame of a film. Figures are caught mid-motion, with strong expressions. In the depiction of the Gigantomachy on the Great Altar of Pergamon, gods and giants battle with fierce energy. Athena seizes a giant by the hair, her cloak billowing like a war banner. Figures twist, clash, and fall, embodying both chaos and divine might. This is not passive myth, but myth transformed into living drama, where every carved figure seems to cry out from stone.

These sculptures did more than depict myths. They created moments of suspense and drama, inviting viewers to imagine what came before and what might come next. In this way, sculptors turned stone into a kind of theater, transforming myth into a living narrative unfolding in the viewer’s mind. This narrative impulse transformed sculpture from passive form into something active and psychological.

When Gods Were Humanised

The myths of the Hellenistic age were not just more dramatic. They were more human. In a world of change and uncertainty, artists made these stories relatable. They remind us that art is not just about presenting perfect ideals, but about reflecting the spirit of its time. In the Hellenistic period, myths stopped being untouchable truths and became windows into human experience.