The Sacred Visual Language of Ancient Egypt

Discover Ancient Egyptian artworks and sculptures which preserved traditions across three millennia

In the heart of ancient Egypt, where the Nile carved its way through the desert, art’s purpose was as a vessel of sacred truth. It was shaped by the belief in ma’at, the divine order that governed gods, humans, and nature alike. Egyptian art served a religious function. It did not seek innovation, but permanence. Pharaohs, considered gods in human form, used art to reinforce their role as intermediaries between the earthly and eternal realms.

For over three thousand years, from the Early Dynastic Period to the fall of Cleopatra’s Ptolemaic line, this artistic tradition endured with astonishing consistency. It survived the rise and fall of dynasties, foreign invasions, and even the arrival of Greek rule.

This is why so much of Egyptian art appears frozen in time. Whether carved in stone or painted on plaster, every image was part of a cosmic script, preserving truth across the ages. Deviating from these sacred forms risked disrupting ma’at itself. The Greek rulers who conquered Egypt adopted its artistic conventions, recognizing that legitimacy required participation in this visual language of the eternal.

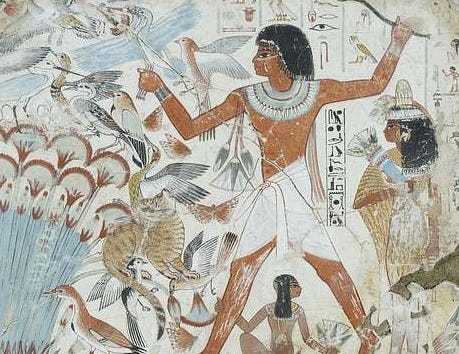

Tombs as Gateways to the Divine

Egyptian tombs were more than burial chambers. They were believed to be portals between worlds. In the Valley of the Kings, pharaohs like Ramesses VI filled their tombs with images drawn from the Book of the Dead, a guide for the soul’s passage through the underworld. In his tomb, the ceiling shows Nut, the sky goddess, arching protectively over the cosmos, her star-filled body framing the journey of the sun god Ra through darkness and rebirth.

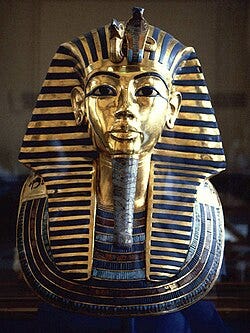

The tomb of Tutankhamun, discovered in 1922, brought this vision to light. Though he died young and ruled for only a short time, the treasures buried with him were breathtaking. His golden funerary mask, with its serene expression and inlays of lapis lazuli, quartz, and obsidian, was not meant to depict his true likeness, but his ideal form. In death, Tutankhamun was transformed into a divine being: eternal, perfected, and radiant.

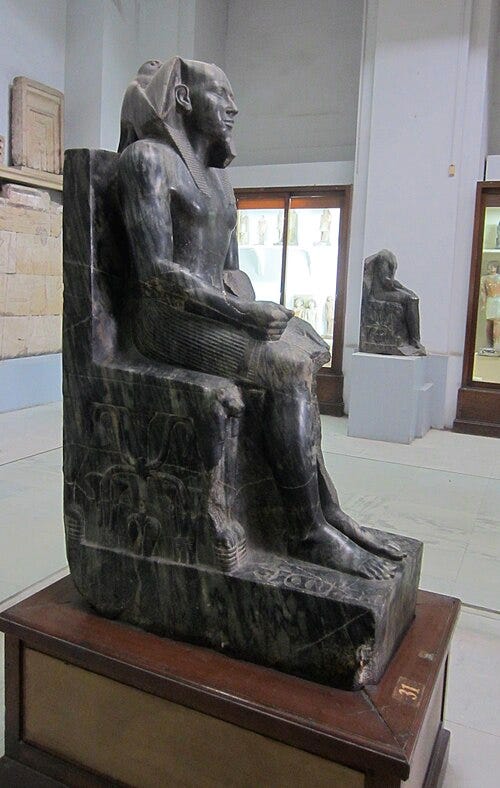

Sculpture and the Idealized Self

Egyptian sculpture conveyed more than physical appearance, conveying status, role, and spiritual significance. The statue Khafre Enthroned, carved around 2570 BCE, depicts the pharaoh seated in a composed, frontal pose. His body is idealized but restrained, emphasizing balance and permanence. The falcon god Horus perches behind his head, its wings wrapped gently around the crown, symbolizing divine protection. The throne is decorated with lotus and papyrus motifs, representing the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. Rather than a likeness of the individual, the statue functions as a timeless image of kingship, designed to ensure Khafre’s continued presence in the afterlife.

The Seated Scribe, created around 2500 BCE and found at Saqqara, offers a rare glimpse into the human side of Egyptian society. Unlike the rigid idealism of royal statues, this figure portrays a middle-aged man with alert eyes, a soft body, and a posture of quiet attentiveness. Though modest in rank, the scribe played an essential role in the functioning of the state. While it departs from the formal iconography of kingship, the statue reflects a broader vision of order, in which even non-royal roles contributed to the maintenance of ma’at.

Art as Ritual Expression

Egyptian art followed consistent patterns because those patterns held meaning. Early works like the Palette of Narmer show the king defeating enemies under the watchful eye of the falcon god. Hierarchical scale, composite poses, and symbolic details all communicated cosmic legitimacy.

In temples such as Karnak and Luxor, reliefs show pharaohs making offerings to the gods, repeating sacred gestures generation after generation. These images were not static repetitions. They were ritual acts, etched in stone. Each one helped renew the divine order it depicted.

Legacy of the Eternal

What remains is not just a record of kings and gods, but a vision of the world as the Egyptians believed it should be. These works were not made for display. They were part of a spiritual system. Each remaining piece is a fragment of a civilization that believed art could hold back time and capture eternity.