What Today’s Illustrators and Artists Can Learn from Joseph Christian Leyendecker

Learning timeless lessons in form, light, and storytelling from a master of illustration

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was one of the most influential illustrators of the early twentieth century. His bold, elegant style helped define the visual language of advertising, magazine covers, and patriotic posters. Best known for his long-running work with The Saturday Evening Post and the Arrow Collar brand, he created iconic imagery that combined strong design, subtle storytelling, and emotional clarity.

For today’s illustrators and visual artists, Leyendecker’s work remains both a source of inspiration and a practical guide. In an era of digital saturation, where clarity and immediate impact are crucial to standing out, his approach is more relevant than ever.

Clarity through Strong Shape Design

Leyendecker mastered the use of simplified forms to guide the viewer’s eye. His illustrations are composed with clean shapes and defined contours that make each figure instantly readable. Even the smallest gestures, such as the curve of a hand or the folds of clothing, convey rhythm and structure.

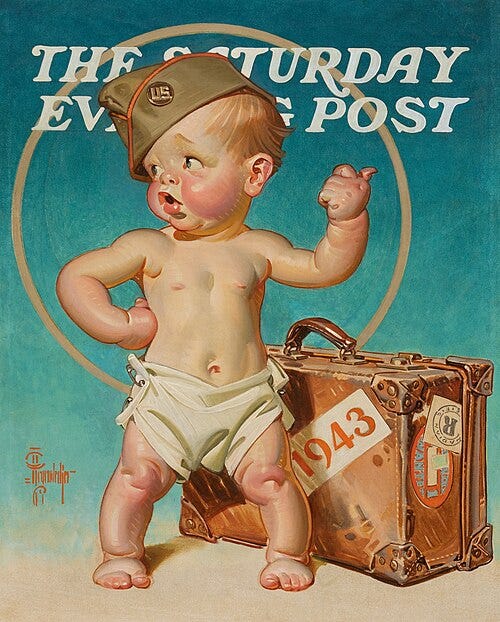

One example is his New Year’s Baby 1943 cover. This piece was created for The Saturday Evening Post but never published, as the editorial team felt it did not convey the certainty of victory needed to boost morale during World War II. Still, it stands as a powerful example of Leyendecker’s skill. The toddler’s form is shaped by flowing curves that fit naturally together, creating a compact and unified silhouette. There is a subtle tension between the sweeping motion of the outer arm and the sharper angles at the elbows and knees. This contrast between soft and sharp captures the unsettling image of a child cast in the role of a soldier. The composition is simple and direct, yet emotionally complex. Its clarity ensures the image is immediately readable, while inviting deeper reflection on innocence, resilience, and the weight of the moment.

This kind of visual economy is crucial for today’s illustrators, particularly those designing for viewing on mobile devices and fast-scrolling audiences. Leyendecker’s work demonstrates how to simplify without losing depth or style.

Using Light with Purpose

Leyendecker’s signature brushwork combines defined, crisp highlights with well-constructed shadow shapes. He often emphasized light on the forehead, nose, and clothing folds, creating sculptural contrast without requiring heavy detail.

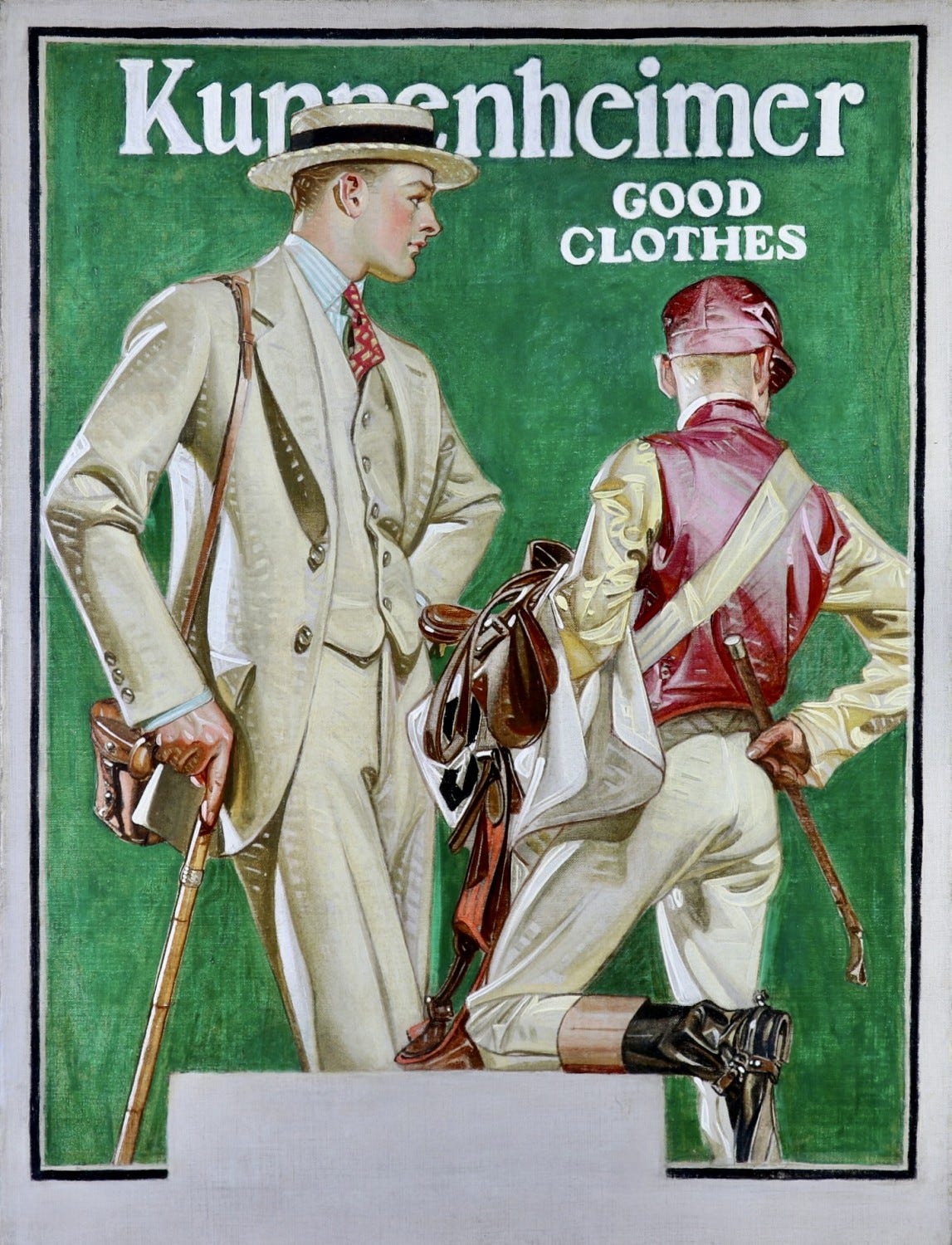

This is demonstrated in a Kuppenheimer Clothing Company advertisement published in The Saturday Evening Post on June 14, 1923, where Leyendecker builds a strong composition through the clothing alone. The illustration features a sharply dressed man with a controlled, upright posture. Light falls across most of the fabric, while shadows lift the folds and separate the layers to create depth and texture. He is paired with another figure whose clothing is looser and more heavily folded, providing a visual contrast that makes the central figure appear even more composed and refined. The result is a design that feels both luxurious and efficient, qualities that remain highly relevant to fashion and advertising illustration today.

Telling Stories through Gesture and Attire

Leyendecker could suggest an entire story without showing any action. His characters feel alive, not because of dramatic scenes, but through posture, facial expression, and composition.

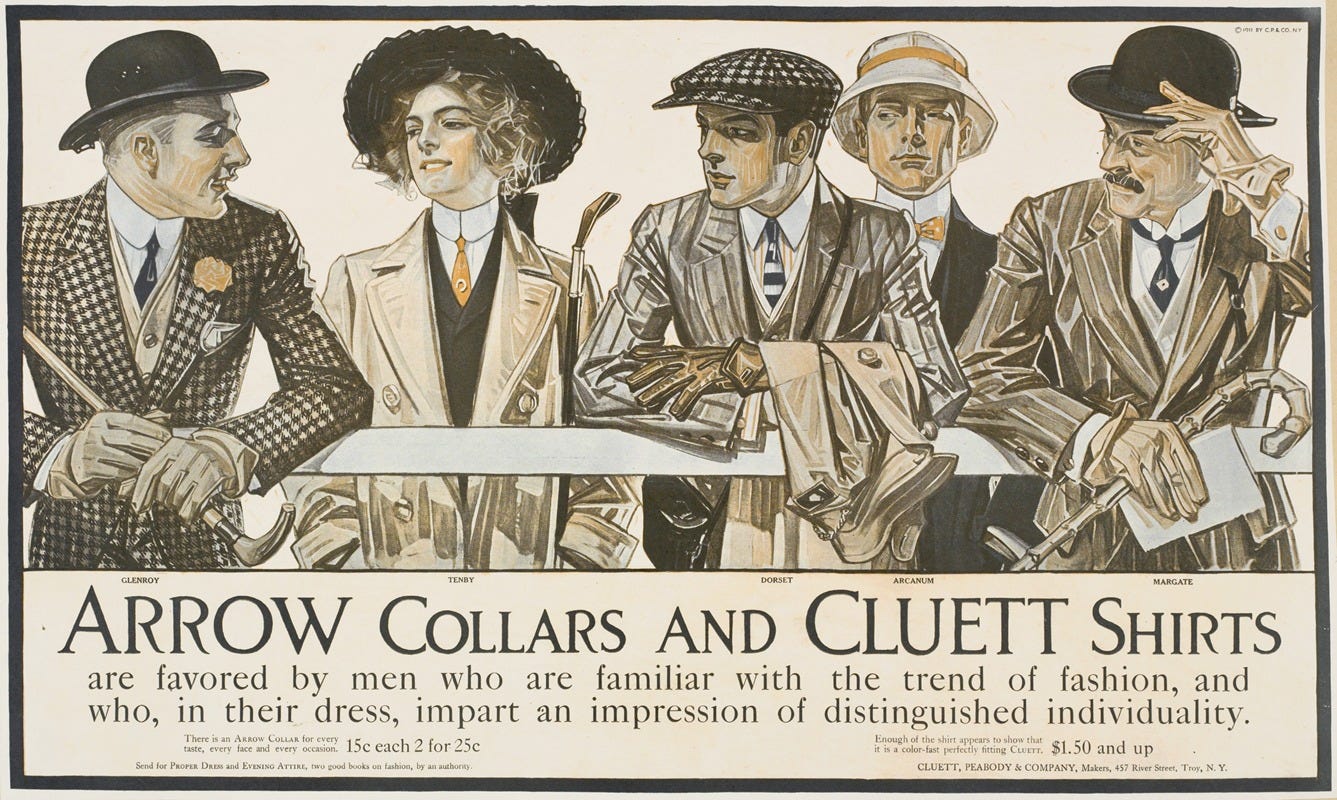

One clear example is his Arrow Collars and Cluett Shirts advertisement, which features five well-dressed figures standing in a compact yet elegant formation. Each character is distinct in both expression and posture, and the blank background gives them more visual real estate. All eyes are directed toward one character, creating a subtle rhythm and the impression of an intriguing exchange. The scene feels composed but never static, with every gesture and glance contributing to the overall mood.

For today’s character designers and editorial illustrators, this piece is a reminder that strong visual storytelling doesn’t require dramatic scenes. Subtle body language can build mood, hint at relationships, and reveal personality, often more effectively than overly dramatized scenes.

Stylization and Elegance

Leyendecker walked a careful line between realism and stylization. His figures were idealized but still believable. In his 1932 piece Easter Walk, he depicts a couple strolling side by side. The man wears a tailored coat and top hat, while the woman is dressed in a flowing gown and bonnet. Their poses are upright and composed, almost statuesque, yet softened by subtle gestures and calm expressions. The forms are simplified, but not flat. They retain volume and elegance without relying on heavy detail. The result is an image that feels both refined and timeless, blending aspirational beauty with quiet realism.

For illustrators today, his style offers an alternative to the extremes of photorealism and cartoon abstraction. He shows how stylization can enhance rather than distort reality, allowing artists to simplify without losing depth or personality.

Why Leyendecker Still Matters

Leyendecker’s legacy lies not only in the beauty of his forms, but in the clarity and purpose of his design. Modern illustrators working in advertising, publishing, or entertainment can gain lasting insight from his work. His command of shape, light, gesture, and stylization offers a timeless guide for creating images that are bold, efficient, and emotionally charged. Even for artists who do not wish to mirror his style, there is much to learn from how he simplified complexity and made forms tell a story. In studying his work, we learn not just how to draw, but how to see.

![J.C. Leyendecker - Easter Walk (1932), [786 x 1024] : r/ArtPorn J.C. Leyendecker - Easter Walk (1932), [786 x 1024] : r/ArtPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3PsW!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F403e1830-1def-4566-bccb-8a6bcfaf8bfd_786x1024.jpeg)