Great Thinkers Define Art: Plato

An exploration of the metaphysical and political reasons why art was suspect in Plato's Republic

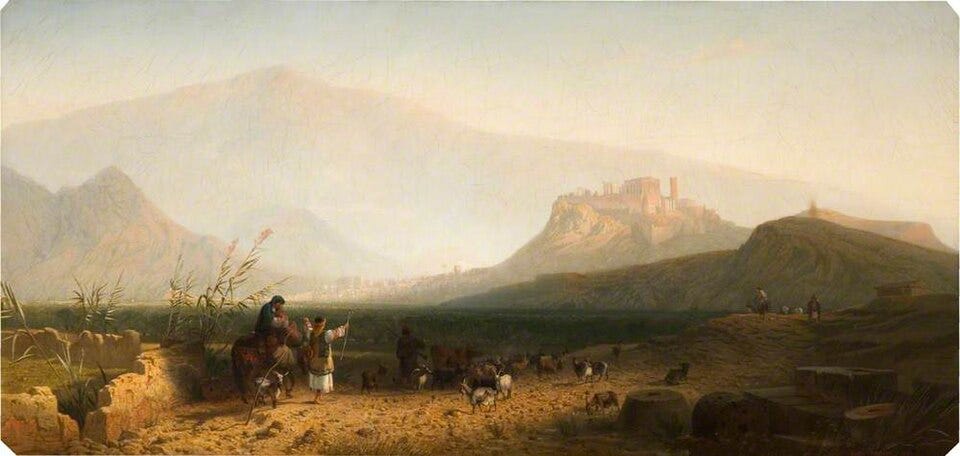

In ancient Athens, art flourished alongside philosophy, democracy, and architecture. Sculptors chiseled lifelike forms from marble, dramatists staged tragedies in open-air theatres, and painters adorned pottery with scenes of gods and heroes. Yet amid this cultural bloom, one voice stood sharply apart.

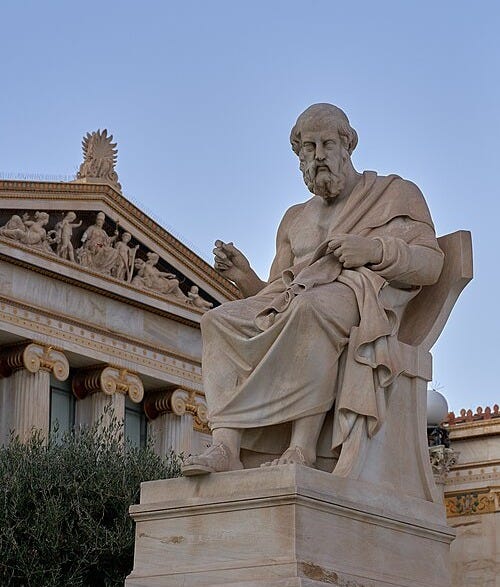

For Plato, art was not a celebration of truth but a dangerous imitation of it. He lived during the 4th century BCE, a time of political change and growing intellectual inquiry. Questions about beauty, justice, and knowledge were becoming central to Athenian life.

Plato's ideas about art were not a side note to his philosophy. They were essential to his vision of a well-ordered society. Through his famous dialogues, especially in The Republic, he made a bold and provocative claim: art, rather than elevating the soul, could mislead it. To understand his position, we must first grasp his view of reality.

Imitation Twice Removed

At the heart of Plato’s critique lies a concern about imitation. He argued that all physical things are imperfect copies of ideal Forms: perfect, unchanging realities that exist beyond the visible world. These Forms include not only objects but also abstract truths such as Beauty, Justice, and Goodness. According to Plato, truly grasping these eternal models requires long study and philosophical discipline.

To make this idea more concrete, Plato uses the example of a bed. First, there is the ideal Form of a bed: the perfect, timeless concept of what a bed is. This Form exists in the realm of absolute truth, which Plato aimed at above all else. Second, there is the physical bed, built by a carpenter. This is a functional object, but it is only an imperfect copy of the ideal. Third, there is the painting of a bed, created by an artist. This is not a real bed at all, but merely an image that imitates the physical bed, which is already a crude copy of the Form.

In this way, art becomes an imitation of an imitation. It is twice removed from the truth and so, the artists do not produce knowledge or deepen our understanding of reality. They create appearances that may seem convincing, but offer no real insight. For Plato, this was no small issue. Art could mislead the soul and strengthen illusion.

The Emotional Power and the Danger of Art

Plato also questioned the emotional effects of art. He believed that poetry, drama, and music stirred powerful passions such as fear, pity, desire, and anger; feelings that, in his view, overwhelmed reason. He describes how tragic poets like Homer and Sophocles led audiences to weep for fictional characters, encouraging a kind of emotional indulgence. In Plato’s ideal society, such unregulated emotion was viewed as a threat to rational order.

As a result of this conclusion, he proposed that most art be censored. Only works that promoted virtue and supported the harmony of the soul would be allowed. Art was to serve philosophy, not compete with it. The artist, like the citizen, had a duty to truth and moral development. Anything else was considered distraction or corruption.

The Artist as a Threat to the Philosopher

Plato’s distrust of art went deeper than its emotional influence. He saw the artist as a rival to the philosopher. While the philosopher seeks truth through reason and dialogue, the artist offers seductive images that seem real but lack substance. A society ruled by art, rather than guided by philosophy, would mistake feeling for knowledge and confuse opinion with wisdom.

Yet here lies a deep irony. Plato’s own writings are among the most literary in the philosophical tradition. He chose the dialogue form, rich with metaphor, character, and narrative. His portrait of Socrates is one of the most vivid figures in Western literature. Despite trying to exile the poets, Plato essentially became one.

Plato’s Legacy and Relevance

Plato’s attack on art seems harsh or unfamiliar to modern sensibilities. But it raises questions that still resonate today. What is the purpose of art? Should it reflect reality, challenge it, or create something entirely new? Can it guide us toward truth, or does it merely empower our illusions?

Artists and thinkers have long wrestled with Plato’s challenge. Some, like Aristotle, defended art as a way to channel and release emotion. Others, like the Romantics, embraced the very passions that Plato feared. Later, Friedrich Nietzsche critiqued and polemicized nearly every aspect of his system.

Plato’s ideas still echo in debates about propaganda, entertainment, and the political use of imagery. By questioning the value and function of art, he forced later generations to think more carefully about what art really does. Whether we agree with his fundamental views or not, Plato remains a cornerstone in the ongoing conversation about beauty, truth, and the deeper purpose of creation.