Leonardo da Vinci's Search for Divine Order Through Art

How one Renaissance genius fused beauty, science, and spirit into a single way of seeing the world.

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the quintessential figures of the Renaissance. He stood apart not only as a brilliant artist but as a true polymath, with expertise ranging from anatomy to engineering. His restless mind refused to be confined to a single discipline. Leonardo believed that understanding the world was a sacred act. For him, beauty and knowledge were never separate. The flutter of a bird’s wing, the spiral of a seashell, and the proportion of a body all pointed to a deeper harmony. To paint truthfully, he believed, one had to first understand deeply. Leonardo didn’t just practice art and science, he unified them.

Reality captured through notebooks

Leonardo’s notebooks remain among the most astonishing records of a human mind at work. Thousands of pages teem with sketches and reflections on a range of subject matters: the flow of rivers, machines for flying, and the anatomy of horses. Yet these weren’t idle curiosities. To Leonardo, every leaf, bone, and shadow carried a logic and a beauty that revealed the divine.

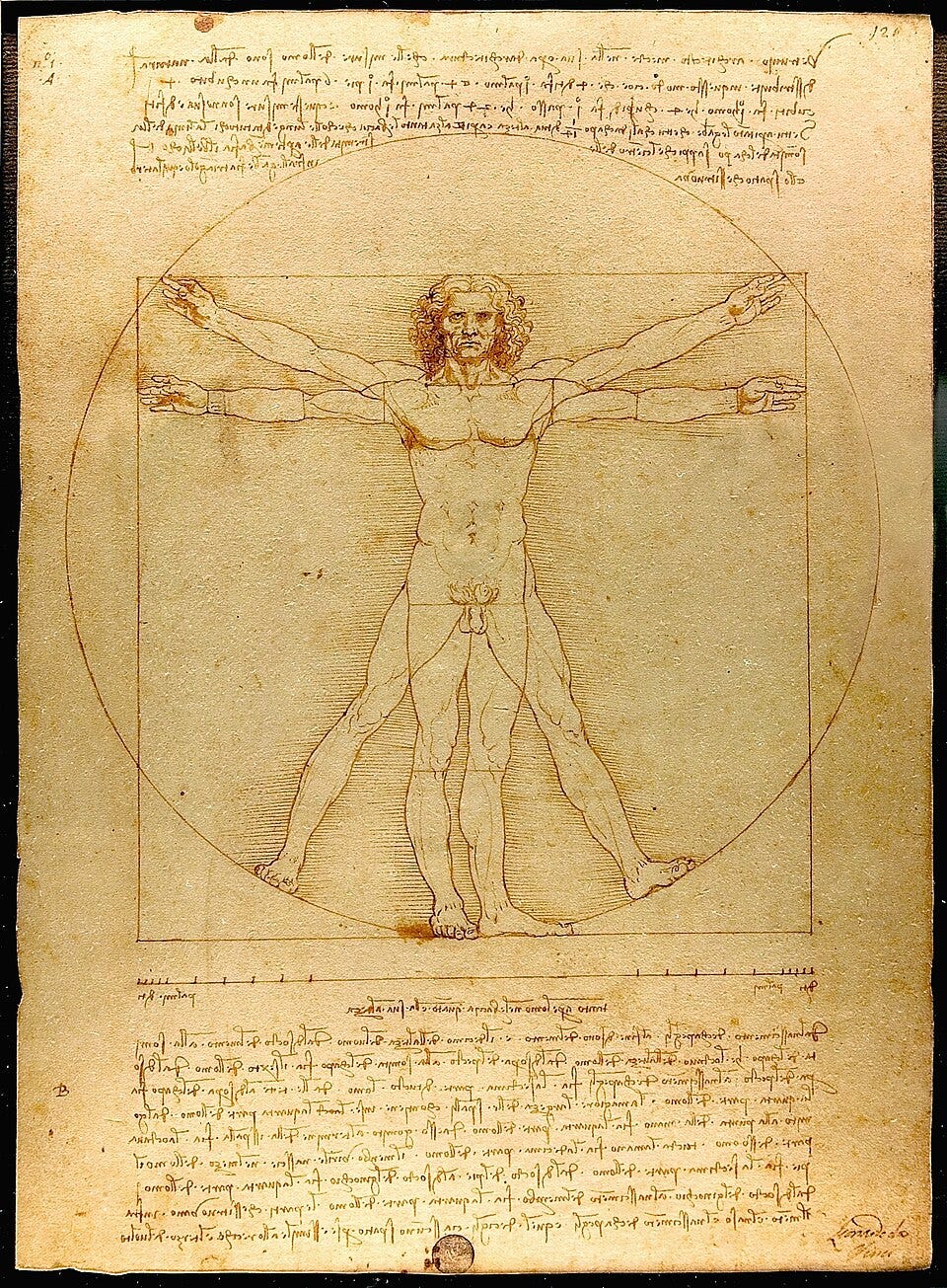

His famous Vitruvian Man, a drawing of a male figure inscribed within both a circle and a square, captures this vision with striking clarity. The piece was Leonardo’s visual response to the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, who believed that the proportions of the human body reflected universal harmony. Leonardo took this idea further, meticulously measuring and sketching the ideal human form with arms and legs extended in two overlapping positions.

The drawing demonstrates how the human body can be used as a unit of measurement, fitting perfectly within two of the most sacred shapes in classical geometry: the square, symbolizing the material and earthly realm, and the circle, representing the spiritual and eternal. Leonardo’s placement of the navel as the center of the circle and the pelvis as the center of the square reflects his deep understanding of spatial relationships and symbolic balance.

The Last Supper’s geometry and grace

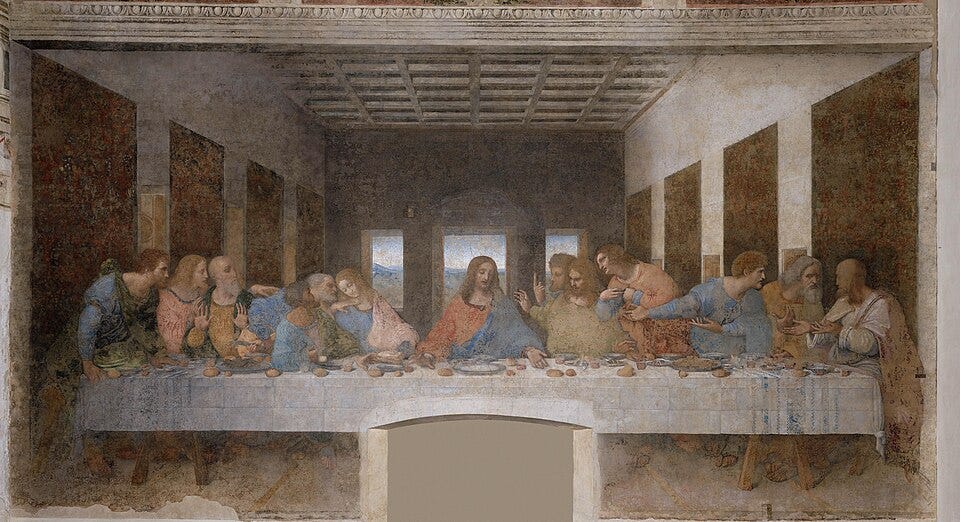

Leonardo’s The Last Supper captures the moment just after Christ’s revelation: “One of you will betray me.” Every line of perspective converges at Christ’s head, making him the stable and balanced center of the composition. The architectural space recedes in precise proportion, drawing the viewer into the room as if seated at the table.

This fusion of geometry and grace lies at the heart of the painting’s power. The scene is symmetrically structured and, at the same time, alive with motion. The apostles are expressive, with hands gesturing and brows furrowed. Yet, all are embraced in a perfectly ordered space.

In this way, Leonardo’s technical mastery becomes a spiritual metaphor. Divine order frames human emotion. Perspective becomes a silent guide, showing the viewer not only where to look, but how to feel.

The subtle harmony of the Mona Lisa

Perhaps no painting is more famous today than the Mona Lisa. At first glance, it appears to be a simple portrait: a woman seated, looking out with a subtle smile. But the depth of Leonardo’s artistry quickly becomes clear. Her eyes are not fixed on a distant point but seem to follow the viewer. The soft haze around her face, a technique known as sfumato, creates a lifelike atmosphere that gently draws the observer in.

Leonardo’s mastery of anatomy allowed him to paint the subtleties that reveal personality. The slight turn of her neck and the softness of her gaze reflect years of study. The composition itself is guided by hidden order. Leonardo employed mathematical principles such as the golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence to structure the image. The proportions of her face, the placement of her hands, and the balance of light and shadow follow natural harmonies that feel intuitively pleasing.

The lack of clear context within the painting invites deeper reflection. Who is she? What is she thinking? Since the Mona Lisa does not offer definitive answers, it encourages viewers to look inward. It becomes less a portrait of another person and more a mirror of the observer. That is why it continues to captivate: it combines scientific precision with psychological depth, offering a quiet mystery that feels both timeless and human.

Learning to look below the surface

Leonardo da Vinci was not content to look at the superficial aspects of life. He wanted to explore the world more deeply. Whether he was sketching a human figure or designing a machine, he tried to identify the patterns and connections that shaped them. In his world, art was not separate from science or philosophy. It was the place where they converged.

Today, we often divide knowledge into categories: art, science, philosophy. Leonardo reminds us how connected these disciplines are, and the importance of integrating insights from each. For him, to see the world’s unity was to love it more deeply, and to better understand the mind of God.