Great Thinkers Define Art: Immanuel Kant

Exploring the belief that aesthetic value arises only when we set aside intention, function, and practical ends

In the Critique of Judgment (1790), Immanuel Kant turned his philosophical attention to aesthetics. He was not interested in taste as a matter of personal preference, nor in beauty as something tied to moral goodness or practical function. Instead, he set out to explain how something could strike us as beautiful without being useful, true, or good in any obvious sense.

For Kant, the key lay in judgment. When we call something beautiful, we are not simply describing a feeling. We are making a claim that seems objective, even though we cannot prove it. Beauty, in his view, arises when the imagination and the understanding enter into a kind of harmony. We experience the form of an object as if it had a purpose, even though it serves none. He described this as the judgment of purposiveness without purpose, and it became the foundation for his theory of art.

The Difference Between Art and Utility

Art, unlike nature, is something humans create intentionally. But not all of the things we make count as art. Kant draws a line between fine art and practical objects. A well-made chair might be pleasing to look at, but if our appreciation is tied to how well it works, Kant would say that it is not beautiful in the strict sense. For Kant, fine art must be judged apart from function or use.

This separation of art from function paves the way for aesthetic ideas: forms that suggest more than any concept can capture. These are not messages or symbols with a fixed meaning. Instead, they stir the imagination, pointing beyond what can be clearly explained. Aesthetic ideas open up layers of thought and feeling that we sense, but cannot fully define through words.

The Artist as Genius

Kant argued that fine art requires a genius, though he meant something very specific by that term. A genius, in Kant’s view, is not simply someone who masters technique or follows rules with great skill, but someone who produces that which cannot be taught or predicted: works that are innately inspired rather than calculated. Their creations express aesthetic ideas that cannot be fully captured in concepts or explained in language, and even the artist may not entirely understand how or why the work came into being. In this sense, genius is nature working through the individual to reveal something deeper than what reason alone could produce.

This view marked an important shift in how society understood artists. No longer simply artisans who refined inherited techniques, the true artist became a kind of visionary, a channel for the expression of ideas that exceed language or reason. A painter like Caspar David Friedrich, whose vast and silent landscapes seem to speak of the infinite, fits this model. So too does Beethoven, especially in his later quartets, where abstract musical structures evoke powerful and mysterious feelings that words cannot capture.

An Intuitive Sense of Meaning

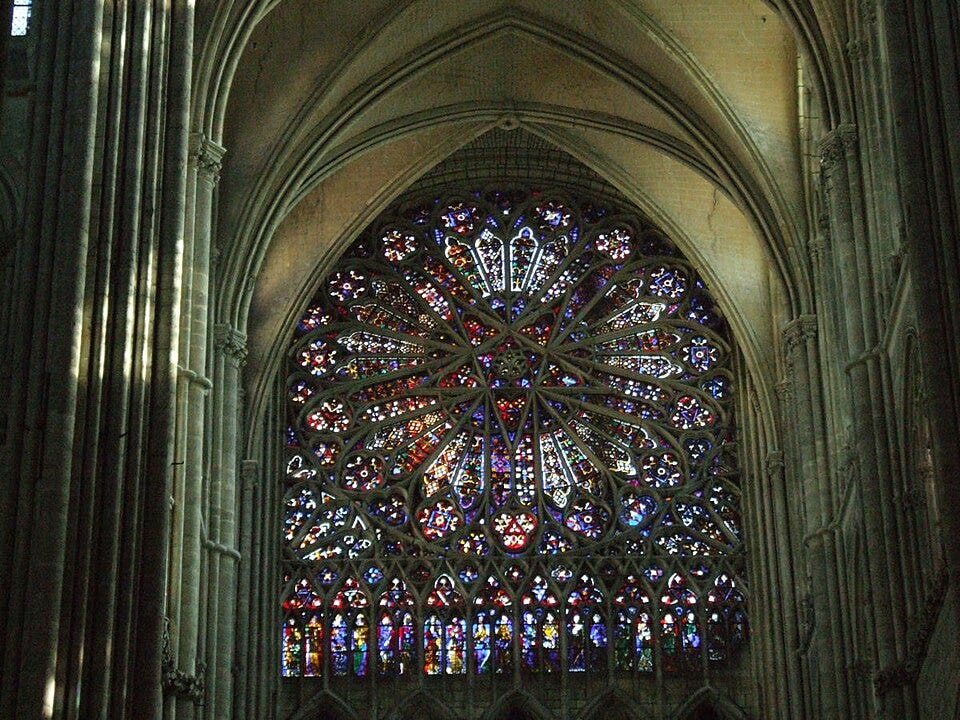

Kant’s theory helps us understand why some works of art feel deeply meaningful, even when we cannot explain why. A Gothic cathedral, with its towering arches and intricate design, can resonate even with those who do not share in its religious meaning.

In seeing this, we experience a sense of inner order. The parts seem to fit together with intention, even if that intention remains obscure. For Kant, this is the essence of beauty in art. It does not depend on story, message, or moral lesson, but on how form and structure engage the mind, inviting reflection without demanding interpretation.

The Legacy of Kant’s Art Theory

Kant’s influence on art theory has been profound. By insisting that art be judged independently of morality or function, he helped shape key movements like Romanticism, Symbolism, and Modernism. His ideas paved the way for abstract artists such as Kandinsky and Mondrian, who sought to communicate through color, line, and composition rather than subject matter.

More broadly, Kant’s view of the artist as a channel for aesthetic ideas reframed art as a form of philosophical expression. He did not offer a checklist for what counts as art, but instead showed why art matters. It is not important because it teaches lessons or serves a purpose, but because it gives us an experience of inner freedom. In art, as in beauty, we encounter form that feels meaningful, even when we cannot explain why.